The Science of Hypertrophy Training

Estimate Reading Time: 25 min

What is Hypertrophy Training?

Hypertrophy training in its simplest form is working to increase the size of your muscles, a benefit I’m sure most of us want from our training. In this article, I’ll provide a deep dive into the current literature on hypertrophy training and give you some practical guidelines to help you get as jacked as possible!

Of course, increasing the cross sectional area and volume of muscle mass is the main benefit of hypertrophy training (overall aesthetics). However, this comes with a host of additional benefits like…

Improved Body composition

Increased bone mineral density

Increased connective tissue strength

Improved glucose regulation

Increased general strength and ability for activities of daily living (ADL)

Improved mobility

And more

Training Parameters

Let’s break down what the current literature suggests for each training parameter for hypertrophy training.

Volume: Defined in this context as sets and reps. Generally, you want to increase your volume over time to maximize adaptations. You can think of volume as your adaptation multiplier. As volume gradually rises, your potential for greater adaptations rises to an extent (Schoenfeld et al., 2019). The current recommendation is to complete 10 - 20 sets per muscle group per week and note, this does not include your warm-up sets. I know that for some of you 10 - 20 sets per week sounds quite low, but it’s important to understand this in the context of intensity, which we’ll touch on shortly (Schoenfeld et al., 2016). In terms of repetitions, the general recommendation is 5 - 20 reps per set. This large range is due to the fact that proper intensity combined with increased volume over time is needed to stimulate hypertrophy. Know that as your reps get lower, you may need to allocate more sets to produce an appropriate hypertrophic stimulus. So long as volume and intensity are equated, you can receive similar hypertrophic responses across a wide set of rep ranges. In terms of sets per exercise, generally 2 - 6 sets is sufficient to help you achieve your goal of 10 - 20 sets per week.

Example: 3X10 on bench press could be just as beneficial as 5X6 (both are 30 reps) so long as they are done at a similar intensity.

Frequency: This is the number of sessions you target a particular muscle group per week. Think of training frequency as a volume allocation tool. You can technically do all 20 sets of chest for the week in 1 session but think about how that will negatively impact the quality of your sets and ability to recover. Generally, you want to hit each muscle group at least 2X / week, but you can of course do 3 - 4X / week to help with increasing volume, lowering fatigue, and managing the length of the session to fit your needs (Schoenfeld et al., 2016).

Intensity: Defined as the difficulty of a particular exercise. I like to use reps in reserve (RIR) for myself and my clients since it has a subjective component to it and is easy to understand. You can also use RPE or percentage of 1 rep max (%1RM) as tools for gauging intensity. Intensity is one of the driving factors for hypertrophy because you need a good amount of mechanical tension and stress to stimulate muscle growth. Using %1RM as a measure of intensity, however, can negatively impact your training since you’re following an intensity prescription from a past performance and using that for all future training. Additionally, you won’t know your 1RM for every single lift unless you test it, which isn’t practical. Also, your 1RM fluctuates on a day to day basis and should ideally go up over time as you train. Take these 2 examples as a further illustration as to why %1RM may not be ideal for measuring intensity.

You do 3 sets of 8 - 12 reps on bench press at 75% of your 1RM (sounds plausible on paper). Let’s say however, that on this particular training day you’re feeling extremely fatigued and weak. You do your first set at 75% if your 1RM and you can only do 6 reps. Now your volume has been compromised due to the subjective load being too heavy for the day.

Another example is you’re doing hack squats for 4 sets of 10 - 15 Reps at 70% of your 1RM. Say you get to 15 reps and thought the weight was super light and could’ve done 8 more reps no problem. Now you aren’t getting enough stimulus for this particular exercise.

By using RIR, you can determine if there’s a need to increase or decrease the load to set to ensure a proper training stimulus. Generally you want to have a RIR of 0 - 4 for your working sets. This scale takes time to learn, but know that 0 RIR means failure (no more reps), and 4 RIR means 4 reps shy of failure, which is pretty intense. You’ll get better at gauging this over time, just know that around RIR 4 you should notice a significant decrease in the velocity of your lift. If you’re unsure what failure feels like or if you’re not confident in your internal assessment, take a simple and safe exercise to failure like a chest press or leg extension. I will use this strategy with my clients who may be struggling to gauge RIR. I’ll have them do a set of an exercise, ask them the RIR right then and there, and then ask them to go to failure and see if the two numbers line up. Lastly, some research has shown that smaller muscle groups (biceps, calves, etc.) may benefit from taking the sets closer to failure (RIR 0 - 1) (Lopez et al., 2020).

Range of Motion (ROM): In general, a full range of motion is going to be most beneficial across most lifting goals. For hypertrophy training, utilizing a full ROM for the movement will maximize motor unit recruitment (MUR), allow you to maintain good mechanical tension, work on improving strength, and overall improve your functionality for activities of daily living (Andersen 2021). There is some interesting research in the area of different parts of ROM training for hypertrophy. One study showed that holding an exaggerated calf stretch produced significant hypertrophy in trained individuals (Warneke 2022). The potential mechanism was hypothesized to be mechanical tension of static stretching mimicking that of resistance training. This idea of training under a long eccentric movement has been examined a few times in recent literature and does show some promising outcomes. What we seem to find is that if you had to pick a particular range of motion and determine which is the most important, you could begin to make the argument that the longest or most exaggerated part of the eccentric is vital. fiI would still advocate for full ROM since it has similar benets and other carry over into ADL and strength, but this research could be promising for rehab settings and the utilization of special or advanced training techniques like isometrics, prolonged and intense static stretching, etc. (Wolfe et al., 2022).

An example of how you can manipulate range of motion in your favor is the single arm cable bicep curl in fixed shoulder extension.

Tempo: is the cadence or pace of each rep during an exercise. As we just discussed, mechanical tension appears to be an important factor for hypertrophy given the current literature. Because of this, it would be beneficial to ensure we have a controlled and full eccentric movement, a strong concentric movement with maximal intent, and perhaps a pause between the phases. A general rule of thumb is to have the eccentric be 1 - 3 seconds in length.

A maximal concentric allows stimulation of more motor units and type two fibers. It may also allow you to lift more load, which can have a small, but non negligible impact on training volume.

Pauses between the eccentric and concentric phases can be beneficial to ensure you aren’t doing cheat reps. Know that you don’t want to use pauses as a means of releasing tension during the lift. Take a bench press as an example, When the bar touches your chest, it’s easy to take a pause for a moment or two and lose tension before the concentric portion of the movement. Instead I would recommend lightly touching the chest but not letting the weight relax on your body.

Specificity: The principle of specificity states that your body will adapt to the stimulus you place upon it. As a simple example, if you want to work on running a marathon, it’s a good idea to run a lot. If you want to improve your 1RM on squats, you’ll need to squat heavy. Hypertrophy is no different. In the context of gaining muscle mass, you’ll want to structure your training in a manner that reflects your aesthetic goals. For example, if you want to focus on your chest, you’ll want to ensure your overall frequency and volume favors chest based training. You may need to have other muscle groups on maintenance so you can devote more time and attention to training a particular muscle group. This all depends how much time you have and your ability to recover, but I would say a safe rule of thumb if you want to prioritize certain muscle groups is to pick 1 - 2 per training cycle (Gentil et al., 2015).

Exercise selection: Similar to specificity, you’ll want to select exercises that best support your goals, training needs, equipment availability, etc. As a general rule of thumb, you’ll want to do a combination of compound and isolation exercises that are specific to the training goal for that day. You’ll want to select compound lifts first since they are generally the most demanding on the body, but you can do isolation based exercises first if you’re specifying certain muscle groups in your training block. Although this may make other lifts more difficult later on in the session you’ll want to prioritize the target muscles first while you’re fresh and able to put the most effort into the session. Additionally, You’ll want to select exercises that best target the muscle for you while managing systemic fatigue.

For example, a barbell back squat is a great exercise for developing the quads, but is it more productive compared to a selectorized leg press? Both exercises involve the ankles, knees, and hips with the primary focus on the quadriceps however, the barbell back squat (being a free weight movement) requires a lot more stabilization, coordination, skill, and demand of other muscles. It might be the case that for some people other parts of their body like their back musculature gets fatigued before their quads do in a back squat. For this reason, you’ll want to select exercises that target the primary muscle while limiting fatigue on other areas.

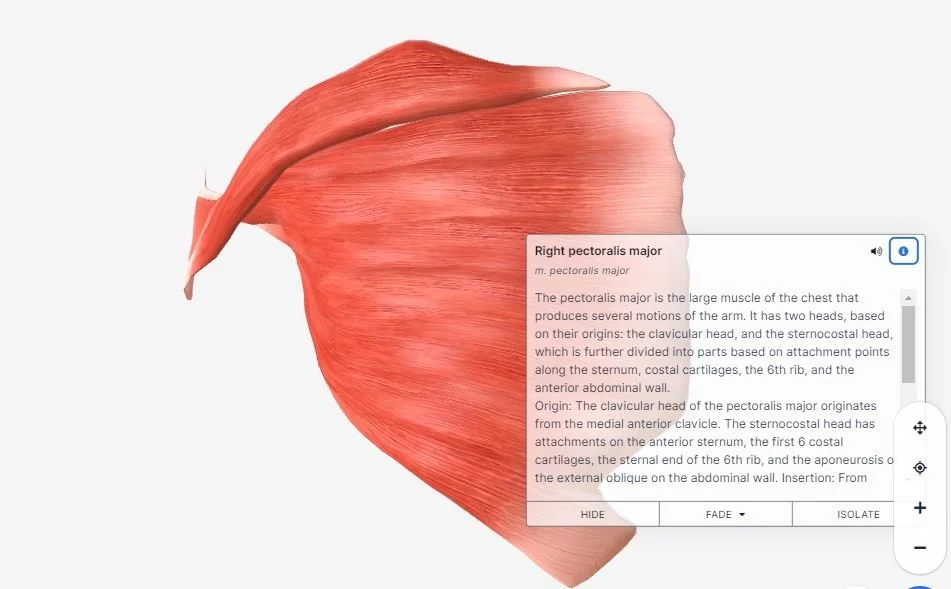

You’ll also want to ensure that you are utilizing the muscle in multiple ways since several muscles have more than one function. For example, the pectoralis major is primarily responsible for horizontal adduction (like in a seated cable fly). However, this muscle is also responsible for flexion and internal rotation of shoulder, so inclined and overhead pressing variations can also be utilized to target this muscle. You don’t have to go crazy and have an exercise for every single function, but you do want to have some diversity in your exercises to ensure you can develop the muscle in a more wholistic manner.

Lastly, you want to pick exercises that help you feel the target muscle. If you’re doing hack squats and you always feel them in your knees despite selecting an appropriate load, controlling the movement, and having solid form, maybe that particular movement doesn’t jive well with your anatomy and physiology. You’ll need to experiment and figure out what movements feel best for you to maximize your training.

Rest Periods: There is no magic formula for how long you should rest between sets. The two important factors to consider are the amount of time you have to train, and general recovery time. The main goal is to take as much rest as needed so that you are physically and psychologically prepped to perform well during the next set. For example, if you only have an hour to train in the gym, taking a 5 min rest between exercises may not be feasible. conversely, if you only take a 30 sec rest between sets chances are your performance is going to plummet, which will negatively impact your training volume since you’ll need to lower the reps, weight, or both. A safe guideline is to take about a 2 - 3 min rest for your main compound lifts and a 1 - 2 minute rest for any accessory movements (Schoenfeld et al., 2016). If you’re out of breath between sets despite taking a 2 -3 minute break, this may be an indicator that you could benefit from some general conditioning or may need to shorten the rest period slightly to build better work capacity in your session.

Recovery

During training you’re actually breaking down your body. The repair and ultimate growth of muscle comes from our recovery when you’re not training. Let’s go over the main concepts of recovery, specifically for hypertrophy training.

Diet: Diet is a big part of the game, and of course there are several nuances. This will all depend on your individual needs, training status, access to food, and meal preferences among other factors. Please note when it comes to diet, you’ll always want to consult your doctor and a Registered Dietitian.

Calories: You’ll need to be in a bit of a caloric surplus to generate substantial muscle growth. This doesn’t mean you can’t grow muscle at maintenance, or even in a caloric deficit, but know that it becomes more difficult. Those who are new to lifting can get away with surplus, maintenance, or a deficit and still experience solid gains, however, once you develop a good foundation for training, your body will require extra resources in the form of calories to add additional lean tissue to your body. If you’re new to training simply ensure you’re getting nutritious food with high protein and you should be good for awhile. I’d recommend maintaining this pattern of maintenance until your rate of gains plateau. If you’re an experienced lifter and are struggling to gain mass despite solid programming, it may be time to increase your caloric intake! One strategy is to do an inventory of your dietary pattern for a week using a diet journal or app like MyFitness Pal to gauge your caloric intake. From there increase your calories by 300 -500 per day. Generally this will lead to a rate of weight gain of about .5 - 1 lbs. per week. Adding calories in this fashion can be beneficial for adding mass gradually and limiting the amount of body fat accumulation. Know that you will put on some body fat, and that’s ok! The point here is to put on as much lean tissue as possible, go to maintenance, and then cut down your body fat, if you so choose to, and repeat the cycle.

Protein: Protein is the building block of muscle! It’s no surprise that protein is of top importance when doing hypertrophy training. The current guidelines suggest for most individuals to consume .8 - 1.5 g. per pound of body weight. Additionally, it can be beneficial to spread this protein throughout the day due to your body’s ability to only process a certain amount at a given time. Don’t concern yourself with the “anabolic window, just ensure you get enough protein in throughout the day and you should be good to go (Phillips, 2016).

Leucine: this amino acid has been shown to be beneficial in muscle protein synthesis (MPS). The general recommendation is to get 3 - 4g. / meal. You can take a supplement to help reach this goal or find it in foods such as poultry, pork, certain fish, beans, milk, cheese, seeds, and eggs.

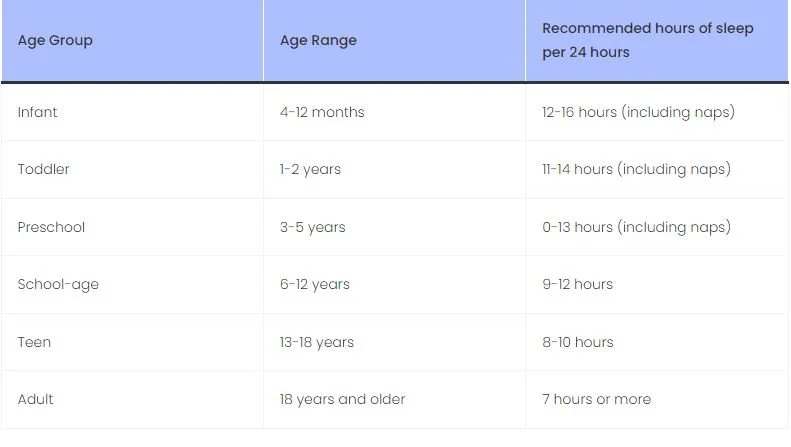

Sleep: We could all use more sleep, right!? Ideally, you’ll want to get between 7 - 9 hours of sleep to help you recover from your training and allow your body to repair itself and add more lean tissue. Naps can also be a great way of getting in the adequate number of hours, but ideally you want long term, uninterrupted sleep (National Sleep Foundation). Some ways to help you get better sleep is to practice good sleep hygiene such as…

Set your room to an appropriate temperature

Avoid stimulants before bed

Having a consistent sleep schedule

Minimizing light and other distractions (phone, T.V., etc.)

Stress: Stress mitigation (both physical and psychological) can be a huge benefit for recovery. Of course when we train, the goal is to stress our body just past it’s current capacity to produce adaptation. In general however, we don’t want to exceed that limit on the regular since it can lead to decreased performance, lack of motivation, pain, injury, and other negative consequences. Some strategies to help mitigate stress are as follows.

Physical Stress: Structure you’re training in a manner that works with your schedule but also honors your body. For example, it may not be the best idea to have your most difficult lower body session at 10pm and then a tough upper body workout at 6am the next day. You can utilize modalities like stretching and self myofascial release for the feel good effect as well. Though these strategies don’t lead to actual recovery, the feel good effect is something that can be leveraged in your favor.

Psychological: Practices like reading, writing, and meditation can be very helpful to calm your mind. Additionally, participating in hobbies and activities you enjoy can be a great mental boost for you.

Other Considerations:

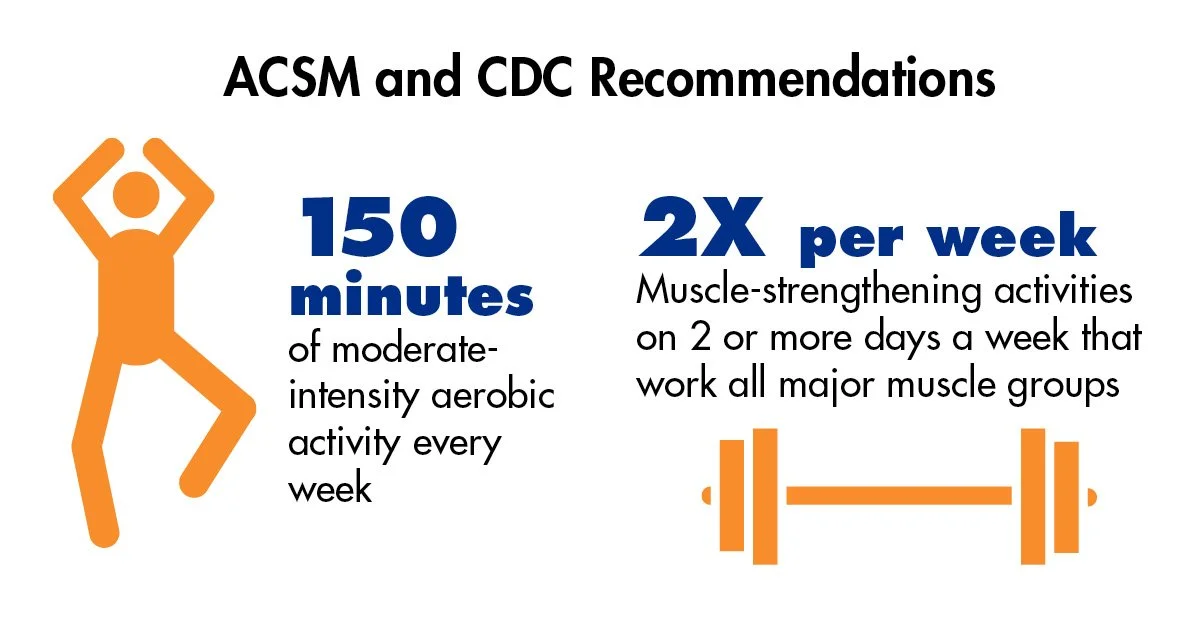

Conditioning: While the main focus for building muscle mass should be progressive resistance training, general conditioning should also be incorporated. Conditioning provides us with unique health benefits like improved cardiovascular health and greater endurance. It can also be a great tool to help with improving body composition. In terms of how much cardio you should do, the goal is to hit ACSM’s guidelines for cardiovascular fitness, which is 150 minutes of moderate or 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity.

Moderate physical activity: RPE 4 - 6 or 40 - 60% max heart rate

Vigorous physical activity: RPE 6 - 8 or 60 - 80% max heart rate

Interference effect: Historically, it was thought that cardio could contribute to decreased adaptations due to metabolic pathways like mTOR leading to muscle degradation. This is more so true for long duration low intensity cardio done in excess rather than simply meeting ACSM guidelines. You’ll also want to structure your training in a way that doesn’t impact your resistance training since that is the primary focus of hypertrophy training. For example, if you want to do interval sprints on the assault bike for cardio, I wouldn’t recommend doing it on the same day as your leg day, or if you absolutely have to, ensure you train weights first, then do conditioning to not impact your lifts as much.

Deloads: Through the course of your training, there will come a point where it’s impossible to simply add more sets and reps. Because of this, you want to build volume up over time to a peak, deload, and then swap your exercises, and then run a new program. Generally 6 - 10 weeks is a good rule of thumb for structuring training blocks, ensuring that the last week is extremely difficult in regards to intensity and volume. Good indicators of needing a deload are slight decreases in performance, lack of motivation, and excess fatigue among other factors.

New to Training: If you’re someone who wants to get as big as possible but you currently don’t participate in resistance training there’s no need to do specific hypertrophy training. Simply doing general fitness and hitting the ACSM guidelines for physical activity will be sufficient for you to see results. You should continue doing general fitness training until you hit a plateau, at which time you can then specialize your training using the information in this blog post.

Sample Program

To sum up all the principles discussed above, here is a sample 4 week program for someone who can train 5X / week. Let’s assume this individual has 1 year of training experience with resistance training and is simply looking to increase their overall muscle mass. I’m going to have this individual do 2 upper body days, 2 lower body days, and one day of low intensity steady state (LISS) training.

References

Andersen, V., Paulsen, G., Stien, N., Baarholm, M., Seynnes, O., & Saeterbakken, A. H. (2021). Resistance training with different velocity loss thresholds induce similar changes in strength and hypertrophy. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. DOI:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004067,

Gentil, P., Soares, S., & Bottaro, M. (2015). Single vs. multi-joint resistance exercises: effects on muscle strength and hypertrophy. Asian journal of sports medicine, 6(2).

Lopez, P., Radaelli, R., Taaffe, D. R., Newton, R. U., Galvão, D. A., Trajano, G. S., Teodoro, J. L., Kraemer, W. J., Häkkinen, K., & Pinto, R. S. (2021). Resistance training load effects on muscle hypertrophy and strength gain: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 53(6), 1206 - 1216. DOI:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002585.

Phillips, S. M. (2016). The impact of protein quality on the promotion of resistance exercise-induced changes in muscle mass. Nutrition & metabolism, 13(1), 64.

Schoenfeld, B. J., Contreras, B., Krieger, J., Grgic, J., Delcastillo, K., Belliard, R., & Alto, A. (2019). Resistance training volume enhances muscle hypertrophy but not strength in trained men. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 51(1), 94.

Schoenfeld, B. J., Grgic, J., & Krieger, J. (2019). How many times per week should a muscle be trained to maximize muscle hypertrophy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining the effects of resistance training frequency. Journal of Sports Sciences, 37(11), 1286 - 1295.https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1555906.

Schoenfeld, B. J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2016). Dose-response relationship between weekly resistance training volume and increases in muscle mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(11). https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1210197.

Schoenfeld, B. J., Pope, Z. K., Benik, F. M., Hester, G. M., Sellers, J., Nooner, J. L., Schnaiter, J. A., Bond-Williams, K. E., Carter, A. S., Ross, C. L., Just, B. L., Henselmans, M., & Krieger, J. W. (2016). Longer interset rest periods enhance muscle strength and hypertrophy in resistance-trained men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(7), 1805 - 1812. DOI:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001272.

Warneke et al. - Frontiers in Physiology - (2022). Influence of Long-Lasting Static Stretching on Maximal Strength, Muscle Thickness and Flexibility, 10.3389/fphys.2022.878955

Wolf, M., Androulakis-Korakakis, P., Fisher, J. P., Schoenfeld, B. J., & Steele, J. (2022). Partial vs full range of motion resistance training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. https://doi,irg/10.51224/SRXIV.98.