Pain & Physical Activity

In this blog I’ll provide some insight into how you or your clients can participate in physical activity while dealing with pain. We’ll discuss a scope of practice as a coach and outline some practical guidelines for when to seek the opinion or care of a medical provider. Then, we’ll detail some factors than can contribute to the pain experience in general and more specifically during exercise. we’ll briefly introduce how the body is adaptive and how this concept may complicate current narratives around pain and injury. Finally, we’ll provide practical strategies for exercise modification and progression to help you or your client resume training in a safe and constructive manner. Please note that this is not medical advice and if you have any concerns about the pain or injury you’re experiencing to please contact your primary healthcare provider.

Reading Time: 45 Minutes

Scope of Practice

When dealing with pain (and potential injury) it’s important to ensure that you or your client are cleared by a medical professional. Clearance may be warranted if you feel unable to participate in physical activity or experience limitations due to pain. It’s important to be cognizant of what constitutes a red flag symptom, when further medical evaluation is recommended, and what exactly falls within your scope of practice as a Personal trainer or coach. Let’s start with red flags. If there’s any concern of neurological damage (loss of sensation or function of a particular area) that should be an indication of getting a qualified healthcare professional involved. Another cause for concern is pain that is debilitating, sudden and doesn’t resolve (or even worsens) over time. Lastly, anytime you can see visible trauma (from an injury or accident, etc.) that should prime you to contact emergency medical services immediately. Now, say your client doesn’t have any glaring issues that require immediate medical attention, what can you do as their coach? One of the most powerful things you can offer your client in any realm of fitness and wellness is education. At the end of the day, coaches are educators, and it is our responsibility to inform our clients on matters that pertain to their ability to be physically active. A key take away here is to ensure that you combine education with compassion. Using the information from Blog Post 2 is great, but when someone is in pain, they don’t care (and maybe they wouldn’t care regardless) about nociception, Kinesiphobia, and other fancy words. These concepts are important for you as the professional to know, but aren’t necessarily important to the client in the immediate (more on this later). Another pitfall you have to be weary of is trying to “out explain someone’s pain”. Remember, pain is multi-factorial and extraordinarily complex. When someone’s back is bothering them, they may perceive your descriptions of pain as dismissive, even if you’re coming from a place of genuine concern. When someone has a headache, they don’t want to know the process by which a headache occurs or how Advil works exactly. What they care about is getting rid of the throbbing pain in their skull. It’s always important to build rapport, gain perspective, and earn trust before challenging someone’s view on a complex issue, especially while they’re actively experiencing it.

It’s important to ensure you aren’t diagnosing someone’s pain. Unless you’re a licensed professional, you’ll want to stay clear of diagnosing or performing tests for legal and safety reasons. Even if you’re knowledgeable with human anatomy and saw your client roll their ankle in the classic inversion sprain fashion, you still can’t diagnosis their pain or potential injury. We also talked in great length about the power of words in Blog Post 2, especially from those in positions of power. It’s vital to avoid using catastrophizing language like “your knees probably hurt because they went past your toes during your squats” when describing pain. Lastly, you want to avoid forcing your clients to do something they aren’t comfortable with. Yes it’s our job as coach’s to challenge our clients and to be that source of occasional tough love but forcing someone to participate in something they fear or don’t consent to is not professional nor is productive.

What you can do (which we’ll go over in great detail) is provide education to your client. As mentioned, we don’t want to explain all these complex terms on day 1 but over time, as you gain rapport with your client, you’ll want to introduce them to some pain based concepts. Whether pain is impacting your client or you personally, it’ll best serve everyone if you maintain a positive mindset. I know this is easier said than done but having positive outlooks is beneficial in just about any process. By keeping a positive attitude, your client can lean on you for moral support, especially on the tough days. Also, you can and should promote being physically active. Remember, there are costs to being physically inactive, so bed rest should be avoided as much as possible (unless recommended by a medical professional). In combination with promoting exercise, as a coach you have the freedom to modify a multitude of factors to help your client work around their pain to assist with staying active. Lastly, you can keep up with the research on pain and injury. This Article will hopefully be a good starting point in your journey to navigating the complexities of pain and exercise.

The Contributing Factors of Pain

As mentioned in Blog post 2, pain is a very common yet complex phenomenon. We outlined how tissue abnormalities in the spine of asymptomatic populations across the life span is quite common (Brikinji et al 2014) and how an estimated 90% of lower back pain (LBP) is classified as non-specific, meaning there is no identifiable cause (Koes et al. 2006). These are but two compelling examples of how visible abnormalities in structures doesn’t necessarily lead to pain and injury and that pain is quite prevalent in those who have no identifiable tissue damage. There are other biopsychosocial factors (outside of tissue damage) that can cause pain. Clinical depression, which impacts roughly 6.7% of the adult population in America (ADAA) is correlated quite well with pain. On average, 65% of those dealing with clinical depression are experiencing pain (Bair et al 2003). Those who occupy a lower socioeconomic status tend to have a higher prevalence of pain for multiple reasons (Maly et al 2018). Being sedentary, participating in extremely high levels (or inappropriately programmed) of physical activity, and obesity appear to increase recurrence of or onset of LBP (Citko et al 2018). It’s also worth noting that being obese (BMI > 30) may produce a systemic, pro-inflammatory state within the body compared to those who have a “normal” BMI (18.5 - 24.9) and are physically active (Hashem et al 2018). As mentioned in Blog Post 2, perceptions can play a large role in a person’s pain experience. We have data outlining how beliefs and attitudes of healthcare professionals (HCP) regarding lower back pain also seems to impact patient outcomes. HCP’s with a biomedical outlook or fear avoidance beliefs are more likely to recommend their patients limit work and physical activity, and recommend bed rest (DARLOW 2012). This isn’t to say there isn’t a time and place to limit physical activity or even have complete rest but in general this should be a last resort as we know people (on average) aren’t physically active enough.

Pain & Exercise

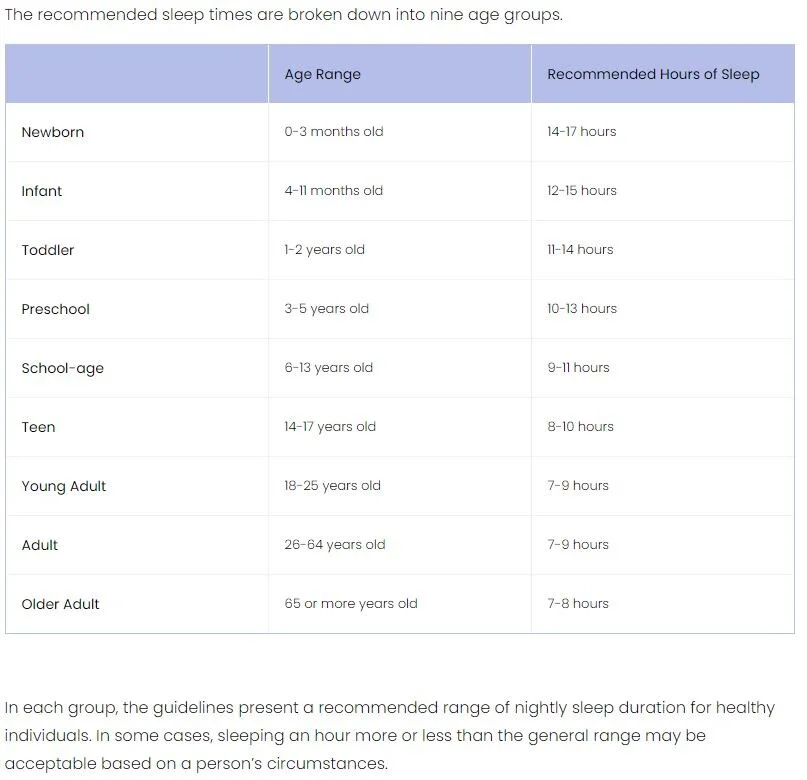

There are of course some considerations when it comes to pain and exercise. First, as mentioned in the Scope of practice section of this article, it’s important to rule out an actual injuries. This isn’t to say you should try and diagnose yourself or your client if you aren’t certified to do so, but if someone’s joint is out of place, or their muscle is swollen and bruised within minutes of feeling pain, or someone smashes a dumbbell on their foot, it may be a good idea to call the session, and go seek medical attention. Outside of what we call a traumatic injury in the gym, there are other factors that can lead to experiencing pain, ones that don’t necessarily mean you’re damaged or something is wrong. You may simply need to look at modifiable factors in your lifestyle or programming. One example of this is sleep. Insomnia has been shown to have a strong relationship with increasing the likelihood and severity of experiecning pain (Sivertsen et al 2015). Taking this into account it’s easy to conceptualize how repeated nights of poor sleep may cause or exacerbate pain, especially when engaging in physical activity which (while safe) produces microtrauma of various systems. Without adequate sleep to aid in the recovery process (among other factors not clearly understood yet) one can see how pain may originate during or after exercise that seems threatening. It’s also worth noting that different people respond in different ways to particular movement patterns. Some people claim that having a more erect, or even slight extension based posture while lifting may aggravate their lower back while others claim a certain amount of flexion during lifts like squats and deadlifts may cause pain like symptoms. It’s important to know your person, check your programming, monitor things like sleep and stress, and adjust exercises as needed for the individual.

Pain vs. Fatigue

When training, it can be difficult at times to differentiate between pain and fatigue, especially for those who are new to exercise. These two phenomenon share similarities. Pain and fatigue can both be uncomfortable, brought on during or after physical activity, and can be exacerbated by biopsychosocial factors. It’s important to note that in order to reap the benefits of physical activity, a certain level of fatigue and discomfort must be achieved in a progressively challenging manner and complimented with adequate recovery. When someone is fatigued, you want to acknowledge how they feel, rule out red flags, check your programming, and carry on. Remember, most people are under-dosed with physical activity. Only 53.3% of Americans self report hitting their physical activity guidelines for cardiovascular exercise. Even more alarming is that only 29.3% of Americans self report reaching the minimum Resistance training guidelines (ACSM 2008) . The last thing we want to tell people is that they’re fragile or they need to move less or worse, have them associate the feeling of exercise as bad or dangerous, thus something determining it as something to avoid. On the flip side, if people are complaining of pain and have other symptoms or aren’t managing other factors well (sleep, stress, nutrition, etc.) you want to ensure you aren’t dismissive, work with your person to modify their lifestyle, and make program modifications as necessary (O’Sullivan et al 2018).

Adaptation

A quick tangent regarding Human Movement and how our bodies react to stimuli. We adapt to gradual changes over time placed upon us by our environment, and thank goodness we do! Our environment isn’t stable or consistent whether we’re talking about the ground we walk on, or the relationships we’re in, nothing in this world is perfectly balanced. Life is a dynamic equilibrium and the human body is no different. Here’s an example I’d like you try right now. I want you stand up and imagine (whether you’re wearing shoes or not) that one of your shoe laces is untied. In whatever way you want (both feet on the ground, using a chair for support, etc.) I want you to pretend you’re tying your shoes. Go ahead, I’ll wait…. Ok, now ask yourself this, when you went to tie your imaginary shoelaces was you back completely and “perfectly straight”? I’m going to guess most likely not. Now, I’m sure most of us will agree that rounding your lower back for 10 - 15 seconds to tie your shoes is no big deal. Ok, what about rounding your back while deadlifting 600 lbs.? Of course it depends on who’s doing the lifting, but the thought of deadlifting with a rounded back has become so taboo that most people may assume that it’s a quick way to get injured and be in pain. Wait, so what’s the difference? If tying your shoes with a little rounded back is ok then why is deadlifting an absurd amount of weight viewed in such a negative manner? What’s the difference between the two? The main difference is the load.

As mentioned, we are adaptive beings. We’ve been tying our shoes all our lives so our bodies have adapted to manipulating our back in various positions to accomplish this task, which makes life much easier. Imagine every time you tied your shoes you had to have a perfectly “neutral” spine, it would be quite cumbersome and limiting to say the least. People may wince at the idea of a 600 lbs. deadlift, so let’s give a more specific example. Let’s say a someone’s deadlift max is 315, and they lift with a moderately “neutral” back. Is it ok for them to round their back a little with an empty barbell? What about with 135 lbs.? WHEN DOES MOVING WITH A ROUNDED BACK BECOME NO LONGER ACCEPTABLE? That’s the problem, the line is constantly moving, because your tolerance to movement depends on training experience, anatomy, and other biopsychosocial factors. Here’s a little secret too, you round your back when you squat or deadlift whether you want to or not, even if it visually appears that you have a neutral back (more on this in future blogs). Here’s another quick example. Let’s say I have “perfect form and posture” while holding a barbell on my back like you would in a back squat. Let’s also assume in this example that the individual’s max back squat is 135 and that they can hold as much as 315 lbs. on their back in a stationary position with no issues. Now, say you load up the bar with 1,000 lbs. and have the individual stand “perfectly upright with the barbell on their back, what do you think would happen? If I had to gamble, I’d say they may collapse under the load and may have broken a structure before they even hit the ground because their body isn’t prepared to deal with that weight. In this example “perfect lifting technique or posture” doesn’t save you from your ability to tolerate a particular load. One day (although 1,000 pounds is world class, but you get my point) the individual can train to tolerate loads that they currently can’t but this takes time, long training history, and proper recovery to get adaptations.

Finally, while biomechanics can make lifts more efficient it’s important to note that what’s biomechanically efficient for one person may not be for another. Yes there are common rules like eliminating moment arms etc. but when working with people it’s important to take into account individual variation and how it may impact their movement. There’s a reason why you see a large spectrum of movement from the general public to the elites. Yes some people are less efficient than others, but so long as you got the basic rules of the movement down, but what matters is your ability to take your talents and limitations and work with them within the parameters of the movement.

Practical Strategies

Now we have some understanding of the contributing factors to pain. So, how do we navigate having pain while training ourselves or when working with a client? Here are a few practical strategies.

Load Management

If you’re a sports fan, you may have heard the term “load management” thrown around quite a bit, particularly as of late in the NBA. The starting small forward for the LA Clippers, Kawhi Leonard, was the focal point of load management conversations the past few years, which propelled this topic into the public sphere. Eckard and company investigated the load management question in great detail with a 2018 systematic review. This study looked at 57 articles and nearly 12,000 participants to determine the relationship between training load and injury. In the context of this review, load was defined as “the cumulative amount of stress placed on an individual from single or multiple training sessions over a period of time”. The study compared measures of external training load (ETL) and internal training load (ITL) to determine which had a greater prediction of injury. ETL can be viewed as load applied to an individual that is inside of their internal characteristics, things like speed of a barbell, reps of a lift completed, etc. Conversely, ITL focuses on quantifying how someone’s body responds to an external load and is divided into objective and subjective measures. Objective measures would be things like heart rate or blood lactate. Subjective measures are self reported ways of measuring load like RPE, or qualitative surveys. When looking at these relationship, the researchers discovered two metrics that were the strongest predictors of injury. Those metrics are session rate of perceived exertion (sRPE) and acute chronic workload ratio (ACWR). Lets investigate each of these in greater detail.

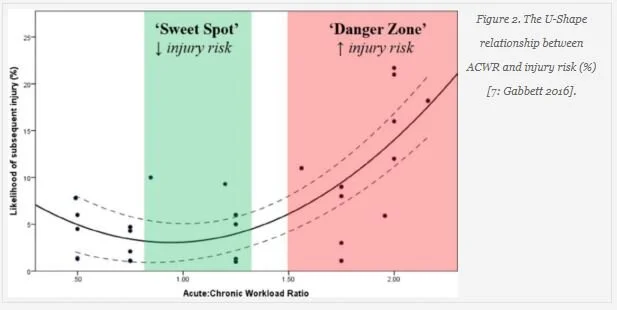

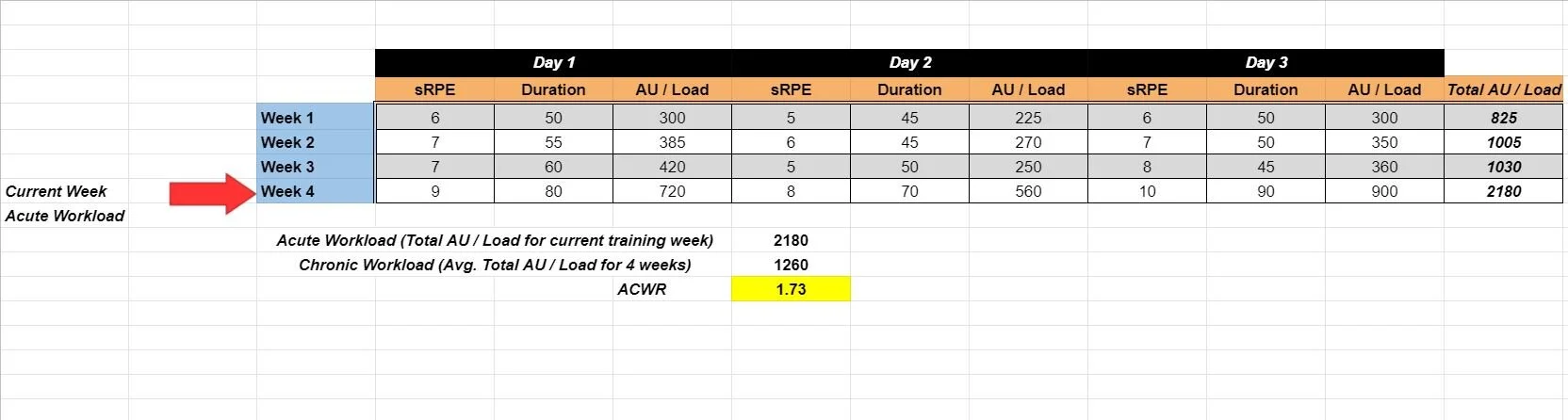

sRPE is the perceived intensity of an entire training session on a scale of 1 - 10. For example, if your workout was to sit on the couch for an hour you’d call that a 1 while running hills for 3 hours non-stop would be considered a 10. The researchers determined that by using sRPE and session duration you can get a value called arbitrary units (AU). These units could then be used with ACWR to determine if your jumps in training load are too much, too little, or sufficient. ACWR is a ratio between acute training (generally a week) and chronic training (generally 4 weeks) load. Essentially, we are comparing the short term or planned workload of our current training week (acute) to our long term, previous training history over the past 4 weeks (chronic). When calculated, we want ACWR to be .8 - 1.3. Less than .8 and the training stimuli may not be sufficient for positive adaptation, while greater than 1.3 (some research may suggest 1.5) and this may be indicative of too large a jump in training load.

Let’s outline exactly how this works with a practical example. Say you have a client that lifts 3 times per week. At the end of each session you ask them “hey, on a scale of 1-10, how tough was today’s workout” record their answer, and record the total duration of the session in minutes. For each day you can use this formula to demine AU or load for a particular training session

sRPE X Duration = AU or Load

After we determine the AU for each day of training we can add all 3 days together to get a weekly (acute) total AU. You then map this process out over the course of 4 weeks. Now, we can calculate ACWR by taking the Total AU of the week we’re currently on (acute) in this case week 4, and divide it by the AVERAGE of all 4 weeks of training (Chronic). As you can see, the ACWR is 1.73, well above the 1.3 - 1.5 upper limit, indicating that the jump in intensity, duration, or combination of the two may have been to great for week 4 (Eckard et al. 2018).

ACWR = Acute workload (week 4) divided by chronic workload (avg. workload of all 4 weeks).

The cool thing about sRPE and ACWR is you can do it with just about any type of workout. You can use this for a weight training session, athletic based workout, or general conditioning. All you need is your clients subjective exertion, a watch, and a calculator! This can get a little technical so setting up a table in Excel or Google Sheets makes life easy. When in doubt, don’t make large jumps in training volume. If you or your client are constantly doing the hardest workout of your life it may be time to modify your program. This concept also reinforces the idea that people can get injured or experience pain from something as simple as poor programming. Say you took a few weeks off and then immediately do a grueling workout with heavy weights. Another example is you’re training your client at a moderate intensity this week and next week’s program has them changing 5 training variables to make the workout more challenging. It’s important to note that sRPE can also be influenced by the factors we mentioned above like lack of sleep and stress, so be sure to take those factors into account. If you or your client experiences pain while doing something extremely challenging it may just be your body telling you that you aren’t prepared for this task at this given point in time. As mentioned above, your body is an adaptive structure, meaning that it will adapt overtime to the demands placed upon it (SAID Principle). However, meaningful adaptation doesn’t occur overnight and requires adequate recovery to benefit from training stimuli. This concept of mitigating large jumps in training load in a practical, individualized manner is what’s known as load management.

Exercise Modification

One way to immediately work on dealing with pain while training is exercise modification. We can modify exercises in a variety of ways, so let’s go over a few examples of what you can modify in a given training session.

Load: Modifying load is usually where I start. As mentioned above, sRPE and ACWR are great metrics for estimating pain and subsequent injury. During a training session, we can modify this by changing the prescribed RPE or RIR, decrease objective measures (weight on the bar, distance covered, etc.), and decrease overall training volume. Placing a cap on the RPE while maintaining other factors like volume will mean the client has a subjective gauge of how to decrease load during their training session. If using this method I generally specify the RPE but use increase in pain and symptoms as a cut off point. For example, say you have a client who complained about a dull, anterior shoulder pain during the entire range of motion of a barbell bench press. If last week you prescribed 3X8 @RPE 8 you could instead program 3X8 @RPE 6, but if symptoms worsen to stop, decrease the load by 5 - 10%, and retry regardless of hitting the prescribed RPE or not. This strategy is good because it gives your clients less load, but also allows for wiggle room if the adjustment isn’t enough in the moment. Another example is decreasing objective measures such as distance covered. Say you’re training a weekend warrior who’s prepping for their first 5K but complains of some lateral ankle pain towards the end of their run. What you can do is decrease their mileage to a point that’s tolerable and then gradually ramp it up over time. Lastly, you can simply decrease training volume. You may need to adjust your training frequency or provide more adequate rest days between training sessions of similar muscle groups (around 48 hours) (ACSM) . Know that You may need to use a combination of subjective and objective modifications in you’re programming, and that’s ok!

Range of Motion (ROM): If modifying the training load doesn’t work I start looking at ROM. The goal is to train within a ROM that doesn’t worsen your symptoms. For example, if your client has nagging knee pain at the bottom of the squat (even during body weight squat) try squatting just above that range of motion. Start with light loads, and gradually increase towards a typical training intensity while maintaining that same ROM. The goal is to gradually introduce that painful ROM under a lighter load (hopeful improving by this point), then gradually get heavier until your client returns to a training load they were using previously.

Speed / Tempo: Sometimes, a muscle or other structure (like tendons) may be sensitive to particular speeds of movement. For example, say you have a client dealing with some discomfort and stiffness in the proximal portion of their hamstring but have no immediate red flags of a hamstring tear. What you can do is try finding a speed that doesn’t aggravate these symptoms and gradually increase it over time. Tempo is another way to modify exercise, like doing an eccentrics or pauses. We have strong evidence showing how eccentrics can have great benefits for those dealing with tendinopathy based issues (Petersen 2011). The cool thing about modifying tempo (if you keep volume the same) is that it forces you to lift less weight and control the speed of a movement, which may assist in not aggravating pain based symptoms and contributes to overall load management.

Exercise variation: Ok, so you’ve tried modifying the load, ROM, speed, and tempo of the movement with no luck. It may be time to try doing a variation of the exercise that’s giving you issues. We want to provide a similar training stimulus that is relevant to your or your client’s goals. For example, if a back squat is causing issues at the knee I may transition to a box squat, if that doesn’t work I’ll move to a goblet squat, then a hack squat, then a leg press. Ultimately, I want to use a variation that is as similar as possible. This gives the body and mind a break from the particular movement while not avoiding the pattern all together. If needed, you can always come back to the exercise that was causing issues at a later time.

To summarize, I recommend watching this video by Alan Thrall. Here he documents an actual injury (and subsequent pain) and how he modified his activity to get back to training.

Gradual, voluntary exposure

If you read Blog Post 2 then you already know why it’s potentially dangerous to intentionally avoid exercises that may have caused you pain at some point. For those who don’t know what I’m talking about, I’d reference the Fear Avoidance Model, Kinesiphobia, and Catastrophizing. In order to work against this vicious cycle of movement avoidance (which has risks in of itself, not just psychological) we’ll reference Psychotherapy 101, which is the use of desensitization. Desensitization is exactly what it sounds like, you’re desensitizing or reducing your reaction to a stimulus. I’m no psychologist, this is merely an example, but if you’re afraid of needles (trypanophobia) the last thing you want to do is avoid them. Avoidance confirms all your fears, preconceived notions, and negative experiences. You are now trapped in this loop of needles are bad and must be avoided, even though needles can do wonderful things like give people medicine. One strategy to deal with trypanophobia and other psychological disorders is to use something called exposure therapy. Exposure therapy is the voluntary confrontation with the thing, situation, or activity you’re afraid of. The key is that the exposure must be gradual, negotiated, and must be safe for the client. Now, we aren’t psychologist, but we can apply these psychological strategies to physical activity. Say your client believes they really hurt their back doing a deadlift and they’re afraid to hinge over with a barbell. You can ask your client “would you be willing to pick an empty box off the floor” or “Would you be willing to pick up an empty box off the floor on an elevated surface”. Your job is to provide a safe environment for your client and to find what they’re willing to do. Once you find an entry point and subsequent success with completing the movement in a manner that doesn’t aggravate symptoms, use that as validation for your client to break the fear avoidance cycle. After a pain experience the nervous system is in a heightened state of stimuli reception but by conducting movement in a manner that the client agrees to be safe you begin desensitizing the body, causing the brain and nervous system to no longer associate the particular movement pattern with being harmful.

As mentioned several times, pain doesn’t automatically mean that you have tissue damage and should stop exercising. While I don’t subscribe to the “No Pain No Gain” Philosophy, we have some compelling evidence that it’s ok to experience some discomfort or pain while training. The main take away is a certain level of pain is acceptable so long as it doesn’t exacerbate current symptoms or generate new and potential concerning ones. Smith and company investigated if training with some musculoskeletal pain symptoms was more beneficial to patient outcomes vs. those who were discouraged in exercises that cause pain. This systematic review and meta-analysis looked at 9 papers with 385 participants and found that in short term there was a small but significant benefit over pain-free exercise in reducing pain. In the medium and long term, there wasn’t much difference between the two. This study demonstrated how exercise can be painful and still be productive. At the very least, it’s no worse than pain free exercise and while some exercises may be painful, you eliminate the barrier of not being able to do certain movements because they hurt (Smith et al 2017). It’s important to know that (like weight loss) training with pain isn’t a linear process, it ebbs and flows. You’re going to have bad days and good days, the important thing is to do your best to not be discouraged by the bad days, and to celebrate the good ones. A single day doesn’t define your progress over a long span of time. If your average pain level went from a 7 to 2 in 3 weeks, but one day you have a pain level of 4 that still shows you’re moving away from a higher pain level.

Most things in life are not a linear process.

Education

It’s important to break the stigma that exercise is inherently dangerous and will lead to injury and subsequent pain. Life in of itself is dangerous and we take risks everyday (voluntarily and involuntarily), there’s no escaping that. What matters is that the benefits generally outweigh the risks and that you’re willing to assume those risks. Let me outline this with some stats.

One study looked at the prevalence of injuries among competitive powerlifters and weightlifters. The study looked at 9 articles with 663 weightlifters and 472 powerlifters. The Injury rate in weight lifters was 2.4 - 3.3 injuries per 1,000 hours or 1 injury every 303 - 417 hours. Say You lift 3 hours per week (3, 1 hour sessions) for 50 weeks out of the year (2 training weeks off for holidays and such). That would equate to 150 hours per year, and 300 hours in 2 years, close to the lower end of 1 injury per 303 - 417 hours. So, you can expect 1 injury every 2 years - 2.8 years. Note that there are various definitions and severities of injuries as well. An injury could be something as simple as torn callus, or stubbed toe. For powerlifters, the injury rate was 1 - 4.4 injuries per 1,000 hours or 1 injury ever 227 - 1,000 hours. Using the same example of training 3 hours per week, we can estimate an injury rate of 1 injury every 1.5 - 6.7 years. These injury rates are similar to those seen in non-contact sports and have lower injury rates than some contact sports. People are generally ok with engaging in various sports but may fear weight training. The ironic thing is that some contact sports are technically more dangerous. (Aasa 2016).

Another paper compared the injury rates of various physical activities. The activities measured included aerobics, walking, gardening, weightlifting, and outdoor bicycling, The study looked at 5,238 participants, which were survey of injury over 30 day period. The study found the following injury rates as % of population sample that reported an injury. (Powell 1998).

Outdoor cycling .9%

Aerobics: 1.4%

Walking 1.4%

Gardening or yard work: 1.6%

Weightlifting 2.4%

This data shows how engaging in conventional physical activity (resistance training and aerobic exercise) is generally quite safe compared to other common activities. As mentioned, it’s important to consider the risk of being inactive and compare with the potential risks of pain and injury. It’s estimated that approximately 8.3% of all deaths can be attributed to not meeting ACSM physical activity guidelines (CDC 2020).

Lastly, we know that when combined with physical activity, education regarding pain and injury can be quite powerful! A common form of education is Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) . Louw demonstrated this quite well in a 2011 systematic review. This review looked at 8 studies (N=401) and determined that PNE was effective in reducing pain ratings, increasing function, addressing catastrophization, and improvement in movement for those dealing with chronic musculoskeletal pain. The duration of these PNE interventions ranged from 30 minutes - 8 hours either in single or multiple bouts of education. The Intervention strategies that were used to present information included the use of pictures, examples, metaphors, drawings, question answer assignments, and questionnaires. Furthermore, the study noted that anatomical / biomechanical models of explaining pain had mixed results in improvement of pain and overall function (Louw 2011). From a practical standpoint, you can assist your client by exploring their thoughts about pain and explaining what you know regarding the subject in a digestible, compassionate manner (see blog post 2).

Building Rapport

One of the biggest things we overlook as coaches is how impactful and important it is to have a great relationship with your client. It’s important to be proficient in program design, cueing, exercise modification, and your various exercise science disciplines, but in my opinion all of that doesn’t matter if the person you’re working with isn’t bought into the process. Long term buy in comes from trust, respect, and a relationship cultivated on wanting the best for your client. Building buy in allows you to use all your knowledge and expertise with little to no resistance, because you’ve taken the time to build trust. Imagine the last time you had a bad experience with a shady mechanic. You take your car in to fix a problem and it seems like your car comes out in a worse condition and the initial issue still wasn’t resolved. Now, if you even go back to that same mechanic again, you’re hypervigilant, constantly questioning, standing over the mechanic’s back, and losing faith in their judgement. This isn’t an ideal situation (for either party) to fix a car. Now, think of a time where you had a mechanic (or imagine) who gave it to you straight but was also kind and happy to have you as a customer. They take the time to listen to your concerns, do their diagnostic testing, determine the issue, explain to you what they think is going on, quote you a fair price (and actually abide by it), take care of the issue and give you some tips on how to potentially avoid the same issue in the future. I bet next time you have an issue you' won’t hesitate to go back to that mechanic. In fact, you might even feel relived knowing your car is in good hands and that you don’t have to worry about ensuring they’re doing a good job, especially if you aren’t an expert in automotive repair.

This whole process of cultivating relationships and trust is all founded on the concept of building rapport. Rapport is simply a relationship established by mutual understanding and trust. If you can build rapport with your client, you can build trust, and if you can build trust you can utilize your knowledge and skillsets to program effectively. Rapport is extremely important when a client is feeling pain because pain can alter someone’s general perception of a given situation. We’ve all heard the saying “you aren’t you when you’re hungry” well, when you’re in pain you may act differently than you would otherwise, because things are hurting and that can be scary. Because people are in this heightened state of fear, anxiety, and physical discomfort, it can be difficult to communicate or implement potential strategies to help alleviate or resolve the issue. If you’ve taken the time, however, to build rapport (a process that never ends) your client will be more receptive to trying the strategies mentioned above, because they trust you, their Coach, to have their best interest in mind and that you will work diligently to find a solution. We also know that rapport has a direct impact on a clients self-efficacy, adherence, and overall pain level. If self-efficacy is high, then the client has greater confidence in their ability to improve their pain status and stick with the training program you’ve assigned them. By improving self-efficacy we can assist clients in getting out of or even bypassing the fear avoidance model, because they believe in their ability to get better. We also see some research in the area of how rapport acts somewhat like a natural placebo, meaning a good relationship and trust has general positive effects on person’s overall health by creating positive expectations (Schwarz et al 2016).

Ok, so we know that rapport is helpful, the question then becomes how do you build it with your client? As mentioned, building rapport is a process that never ends. Just how your friendships and romantic relationships require constant attention, so does the relationships with your clients. Here are some practical strategies to help you build rapport with your client.

Make a good first impression: When you meet a new client for the first time do your best to make the meeting a conversation, not an interview. You also want to ensure you’re enthusiastic and genuine in meeting them.

Get to know your client on a personal and professional level. Ask about their life, family, work, upbringing, likes, dislikes, dreams and ambitions. Likewise, let your client know who you are! Relationships are a two-way street, so be sure to to take interest in your client’s life while also giving them insight into your own.

Ask open ended questions: Open ended questions or conducting motivational interviewing allows you to gain greater insight into a particular topic. This also allows your client to think more critically about the conversation and shows them that you genuinely care about their response since you’ve asked something that can’t be answered with a simple yes or no. Know that your conversations with your client shouldn’t always be about exercise. For some people, that 1 hour they have with a you is a time to let off some steam and you might be the only person they’re able to speak to. I often say Personal Trainers / Coaches are a combination of bartenders and psychologist, people share things with us that they may not tell anyone else and often times look for help or validation from us since they hold our perspective in high regard (obviously we aren’t qualified to be either, but you get my point I’m sure).

Remember and celebrate important thing’s in your client’s life. This is one of those relationship builders that takes minimal effort but produces a great amount of rapport. Remembering and celebrating things like birthdays and personal bests can make your client’s day or even their week. Bringing up old memories (both workout and personal life related) to show you’re paying attention to your interactions and conversations can also go a long way. Even if it seems like something trivial to you, know that it may have meant the world to your client. Client’s may also look up to you and seek your approval and validation, so the more praise the better! As the great Dale Carnegie once said, “Praise the slightest improvement and praise every improvement. Be hearty in your approbation and lavish in your praise.”

Be honest and kind in every interaction you have with your clients” These two attributes must be used in unison when having discussions because solely focusing on one or the other will do your client a disservice. For example, if you take the pure honesty route and leave out kindness when having a conversation with an obese client, you could say “So based on your body fat, waist circumference and lack of physical activity you are at greater risk for developing cardiovascular disease and dying an early death. So you really need to start becoming physically active”. Nothing about that sentence was factual incorrect, but how painful was it to read? Being honest generally doesn’t have much utility if it isn’t paired with kindness because it makes people less receptive to your perspectives. You could be the smartest person in the world but if people think you’re an ass then they won’t listen to you. You’ll get the rare bird every now and again that functions well with blunt honesty but I’d argue they’re far and few. Most people won’t put up with that type of rhetoric and if they did then we wouldn’t need to spend time cultivating relationships, we would simply tell people the facts, convince them, and move on with our lives, but that’s not how things work. On the flip side, if you’re willing to always substitute the truth for kindness and compassion you may end up doing more harm than good. Imagine if you were a client and no matter what you did your trainer said you’re perfect! I’m sure the unconditional love and support is great for a little bit, but if everything is always perfect how are you to know when things need to be improved? If ever time you skipped a workout and your trainer said “that’s ok” how would you feel? Are they being kind, sure, they’re understanding that you may have canceled for a multitude of reasons, many of which may be valid excuses. But without honesty, it’s difficult to be accountable and have those meaningful and sometimes difficult conversations with your client. Of course context matters, and some conversations (or clients in general) require more honesty or compassion. When in doubt however, it’s good to use a combination of the two. It’s a valuable skill to learn to tell the truth without tearing people down.

References:

Aasa, U., Svartholm, I., Andersson, F., & Berglund, L. (2016). Injuries among weightlifters and powerlifters: A systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(4), 211-219. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096037

ACSM information on… a road map to effective muscle recovery. (n.d.). Retrieved May 6, 2021, from https://www.acsm.org/docs/default-source/files-for-resource-library/a-road-map-to-effective-muscle-recovery.pdf?sfvrsn=a4f24f46_2

ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. (2018). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer.

Apa dictionary of psychology. (n.d.). Retrieved May 06, 2021, from https://dictionary.apa.org/desensitization

Bair, M. J., Robinson, R. L., Katon, W., & Kroenke, K. (2003). Depression and pain comorbidity. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163(20), 2433. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433

Brinjikji, W., Luetmer, P., Comstock, B., Bresnahan, B., Chen, L., Deyo, R., . . . Jarvik, J. (2014). Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 36(4), 811-816. doi:10.3174/ajnr.a4173

Citko, A., Górski, S., Marcinowicz, L., & Górska, A. (2018). Sedentary lifestyle and Nonspecific low back pain in medical personnel in North-east Poland. BioMed Research International, 2018, 1-8. doi:10.1155/2018/1965807

Darlow, B., Fullen, B., Dean, S., Hurley, D., Baxter, G., & Dowell, A. (2012). The association between health care professional attitudes and beliefs and the attitudes and beliefs, clinical management, and outcomes of patients with low back pain: A systematic review. European Journal of Pain, 16(1), 3-17. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.06.006

Eckard, T. G., Padua, D. A., Hearn, D. W., Pexa, B. S., & Frank, B. S. (2018). The relationship between training load and injury in athletes: A systematic review. Sports Medicine, 48(8), 1929-1961. doi:10.1007/s40279-018-0951-z

Facts & statistics: Anxiety and Depression Association of America, ADAA. (n.d.). Retrieved May 06, 2021, from https://adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/facts-statistics

Haff, G., & Triplett, N. T. (2016). Essentials of strength training and conditioning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Hashem, L. E., Roffey, D. M., Alfasi, A. M., Papineau, G. D., Wai, D. C., Phan, P., . . . Wai, E. K. (2018). Exploration of the inter-relationships between obesity, physical inactivity, inflammation, and low back pain. Spine, 43(17), 1218-1224. doi:10.1097/brs.0000000000002582

How Much Sleep Do We Really Need? Sleep Foundation. (2021, March 10). https://www.sleepfoundation.org/how-sleep-works/how-much-sleep-do-we-really-need.

Koes, B. W., Van Tulder, M. W., & Thomas, S. (2006). Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. BMJ, 332(7555), 1430-1434. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7555.1430

Lewis, J., & O’Sullivan, P. (2018). Is it time to reframe how we care for people with non-traumatic musculoskeletal pain? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(24), 1543-1544. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099198

Louw, A., Diener, I., Butler, D. S., & Puentedura, E. J. (2011). The effect of Neuroscience education on PAIN, disability, anxiety, and stress in Chronic MUSCULOSKELETAL PAIN. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(12), 2041-2056. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2011.07.198

Maly, A., & Vallerand, A. H. (2018). Neighborhood, socioeconomic, and racial influence on chronic pain. Pain Management Nursing, 19(1), 14-22. doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2017.11.004

Percentage of deaths associated with Inadequate physical activity in the United States. (2018, March 29). Retrieved May 06, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2018/17_0354.htm

Petersen, J., Thorborg, K., Nielsen, M. B., Budtz-Jørgensen, E., & Hölmich, P. (2011). Preventive Effect of Eccentric Training on Acute Hamstring Injuries in Men’s Soccer. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 39(11), 2296–2303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546511419277

POWELL, K. E., HEATH, G. W., KRESNOW, M., SACKS, J. J., & BRANCHE, C. M. (1998). Injury rates from walking, gardening, weightlifting, outdoor bicycling, and aerobics. Medicine& Science in Sports & Exercise, 30(8), 1246-1249. doi:10.1097/00005768-199808000-00010

Schwarz, K. A., Pfister, R., & Büchel, C. (2016). Rethinking explicit EXPECTATIONS: CONNECTING PLACEBOS, SOCIAL cognition, and Contextual Perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(6), 469-480. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2016.04.001

Sivertsen, B., Lallukka, T., Petrie, K. J., Steingrímsdóttir, Ó A., Stubhaug, A., & Nielsen, C. S. (2015). Sleep and pain sensitivity in adults. Pain, 156(8), 1433-1439. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000131

Smith, B. E., Hendrick, P., Smith, T. O., Bateman, M., Moffatt, F., Rathleff, M. S., . . . Logan, P. (2017). Should exercises be painful in the management of chronic musculoskeletal pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(23), 1679-1687. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-097383

What is exposure therapy? (n.d.). Retrieved May 06, 2021, from https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/patients-and-families/exposure-therapy

White, R. (2020, August 11). Acute:chronic workload ratio. Retrieved May 06, 2021, from https://www.scienceforsport.com/acutechronic-workload-ratio/