Pain & Perception

In this blog I’ll outline how pain is currently impacting people, propose definitions for pain & dive into some of its key elements, illustrate its relationship with perception, & provide some data that challenges our current understanding of this phenomenon.

Reading Time: 40 minutes

The Most Difficult Step of any journey is Usually the First

Saying pain and perception are complicated subjects is a vast understatement. I’ll do my best to unpack this complicated subject and will hopefully bring some clarity using the research we have available to us. As mentioned in my first blog, I am by no means a specialist in the field of pain, nor am I a physical therapist or psychologist, I’m simply a curious coach. If you are struggling with debilitating pain or injury please seek medical attention from your physician.

So, where to begin? Anytime I try to tackle an issue I start by clearly identifying a problem, doing my best to define it, look for research on the subject, and then investigate potential solutions. I’d like to start with a quote from the CDC that states, “Chronic pain is one of the most common reasons adults seek medical care, has been linked to restrictions in mobility and daily activities, dependence on opioids, anxiety and depression, and poor perceived health or reduced quality of life” (CDC 2016). The CDC’s claim here is that chronic pain is an issue worth addressing, so let’s back this claim up with some stats. In 2016, 20.4% (approximately 50 million Americans) of the population reported having some form of chronic pain, which is defined as having pain lasting longer than 6 months (correction from Blog 1). It’s also estimated that 4 out of 5 people will experience some form of lower back pain (LBP) at some point in their life. To further complicate things, it’s estimated that 90% of LBP is non-specific, meaning there’s currently no identifiable cause for it (Koes et al. 2006). We also know that about 17% of Americans were prescribed at least 1 opioid prescription in 2016, and of that, 11.5 million people 12 years of age and older reported to have misused one of those prescriptions (CDC 2016). Know that I’m not against prescribed opioids, I’m merely highlighting the prevalence of these substances and their misuse. This information tells us a few things…

A lot of people are in a lot of pain.

We aren’t exactly sure what causes some types of pain.

While medication is helpful, it doesn’t seem to be solving the problem, and can have negative consequences.

1 of the top 7 self-reported reasons for not being physically active is “fear of pain and discomfort” (CDC 2020). I’d also argue that “fear of pain and discomfort” as well as actual injury / disability can lead to other reported barriers like “lack of motivation”, “Finances”, “energy levels” and “social support”.

Definitions

Now that we’ve identified part of the problem, let’s ensure we have our definitions straight. Let’s start by attempting to define pain. First, I want you to take that word, “pain”, and construct a definition that makes sense to you. Now, take a look at the Oxford Dictionary definition below. Did the standard dictionary definition match up with your understanding?

If you asked me 2 and a half years ago I’d probably give you the definition above. I may have added that emotions can also play a roll in pain, but that was the extent of my understanding. I quickly learned that things aren’t that simple, and to this day I’m still amazed at how little I know about the subject.

Even Morpheus the wise knows that pain is a complicated subject. So, why don’t we take the red pill together and see how far this rabbit hole really goes (If you didn’t get that reference, stop reading this blog and go watch the Matrix ASAP)! To get a better understanding of pain I’ll turn to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). Formed in 1973, the IASP is an organization of over 7,000 members from 125 different countries. They exist to support research, education, and clinical treatment, with the goal of creating better patient outcomes for all pain conditions and improving pain relief on a global scale. The IASP attempted to define pain in 1978 as “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage”. That definition was created 42 years ago and still has some important distinctions from the dictionary definition mentioned earlier.

Pain is mentioned as “sensory and emotional”, which suggests that pain isn’t purely a physical phenomenon.

Pain is an “experience”, which implies a subjective component to it. This leads to the relationship with perception.

Pain is “associated with actual or potential tissue damage”, which complicates the association between pain and injury since pain can be present without tissue damage and vice versa.

Recently, the IASP updated their definition of pain to be “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage,” IASP 2020 and added six key Notes to expand upon this definition.

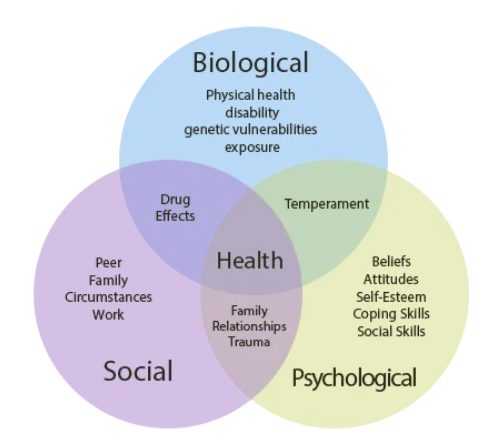

Pain is always a personal experience that is influenced to varying degrees by biological, psychological, and social factors.

Pain and nociception are different phenomena. Pain cannot be inferred solely from activity in sensory neurons.

Through their life experiences, individuals learn the concept of pain.

A person’s report of an experience as pain should be respected.

Although pain usually serves an adaptive role, it may have adverse effects on function and social and psychological well-being.

Verbal description is only one of several behaviors to express pain; inability to communicate does not negate the possibility that a human or a nonhuman animal experiences pain.

The rest of this blog will attempt to outline some of these key points and develop a better framework of what pain is, and how perceptions impact this phenomenon.

The Biopsychosocial Model

Major advances and discoveries in medicine were made throughout the 19th century and into the early 20th century such as the solidification of Germ Theory, which states that microorganisms (pathogens) can invade the body and cause disease. Germ theory came to existence thanks to scientists like Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch. Pasteur was a French chemist who identified that bacteria could get into beer, wine, and even caused products to spoil. Pasteur also discovered how heating products could kill bacteria, which is the process commonly known as pasteurization (science.jrank.org). Pasteur’s work was later expanded upon by German physician Robert Koch, who demonstrated how bacteria could lead to disease. While Pasteur and Koch were investigating microorganisms and their influence with disease, German neurologist and psychiatrist Wilhelm Griesinger made the assertion that mental illness was caused by disease of the brain and nerves (Shorter 1997). The work of Pasteur, Koch, and Griesinger (along with many others) eventually led to Abraham Flexner declaring the Biomedical Model the gold standard of medicine in 1910 (Duffy 2011). This was considered such a revolutionary model at the time because theses biological discoveries and theories led to great developments in western medicine. While this model was an amazing discovery, it wasn’t without its faults. The Biomedical Model unfortunately has a reductionist base, meaning that all pathologies are assumed to be caused by some form of physiological or biochemical imbalance. This means if one can identify the imbalance, one can “cure” or treat the pathology (Strickland et al. 2015). The Biomedical Model’s influence isn’t limited to the pure practice of medicine, it’s also provided the foundation for the general public’s, as well as health and fitness professional’s understanding of pain. Pain is commonly believed to be a purely (or at least primarily in most cases) biological occurrence that can be treated if you merely find its root cause. This cause can be from a number of possibilities like a “tight” muscle, or scar tissue, or “poor posture” (more on these claims in a future post, so back to the subject at hand).

American psychiatrist George Engel decided it was time for the field of medicine to adopt a new model. Engel saw how the biomedical model was based on a reductionist view, which only looked at biological causes and factors of disease. As a psychiatrist, Engel understood that when treating a person you have to address the biological, psychological, and social factors of their being. It was here that Engel created the concept of the Biopsychosocial (BPS) Model of Medicine. This model didn’t eliminate the important biological aspect of medicine, it simply expanded upon it to create a more complete picture (Engel 1977). Biology addresses issues like genetics and physical health, psychology takes into account beliefs and attitudes that an individual has, and the social component outlines how one’s environment, family, and experiences shape who they are. Let’s put this model to the test with real life scenarios regarding pain. Someone gets into a horrific car accident and shatters their femur, I’d guess the pain from that injury is at least 99% biological. You break a bone, so your body notifies you about the injury with a pain response, pretty clear cut. Now, take an example of a person who has had LBP for 20+ years, has a clean MRI, and no history of injury? Engel’s BPS Model demonstrated how things might be a little more complicated than we like to admit.

Pain Vs. Nociception

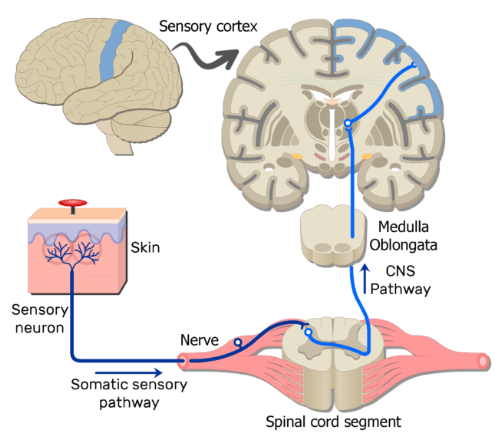

When discussing pain it’s important to define nociception. Nociception is the neural coding process for noxious or potentially noxious stimuli (IASP). These stimuli can be mechanical, thermal, or chemical in nature, and are detected by nociceptors. Nociceptors are found in areas of the body such as skin, muscles, joints, and various organs. Nociceptors are generally classified into two sub-types, which are A delta fibers and C fibers. A delta fibers alert the body to presence of pain, while C fibers produce the intensity of the pain being experienced. When these nociceptors detect stimuli they transfer information to the brain to interpret the data. Parts of the brain involved include the thalamus, hypothalamus, brain stem, somatosensory cortex, and several others (Kendround et al. 2020).

Nociception Pathway

The brain is then tasked with interpreting the information provided by various nociceptive pathways and producing a response. If the brain perceives a threat, a pain experience will be produced in the magnitude and location seen fit. If no threat is present, a pain experience will not occur. One way of looking at this series of events is to view the nociceptors as the messengers, and the brain as the boss who reads all the information and makes all calls. Here’s the tricky part, when the brain is making a judgement call it isn’t relying solely on the nociceptive information. Remember, pain is an experience influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors. This means that the brain will use nociception (biological) data as well as memory, emotional state, cognition, attention, other’s experiences, environment, and much more to decide what to do with the stimulus. The brain can produce a reaction across a spectrum from “Hakuna Matata” (no worries) to “THREAT, DANGER” and everything in between. You can also compare the pain experience process to that of a basketball coach designing a play. Say the coach’s team is down by 1 point and has possession of the ball, so he calls a time out to draw up a plan to score the game winning basket. When making this game plan, the coach will of course take into account what his players (the nociceptors) say and do about the given situation, but the coach must also take into account the time left on the clock, how the defense will respond to a particular scheme, what the defense has done historically, what player has the best chance of making the shot, what happened last time his team was in this situation, and much more!

The Hakuna Matata Spectrum of the Pain Experience

The Pain Experience

The next issue to address is what does it mean when someone is actually having pain? I want to make it clear that I would never deny someone’s experience or say pain isn’t “real” or that it’s “all in your head” as this line of thinking can be dismissive and factually incorrect. It’s important to know that the line between subject and objective reality can often be blurred when working with people because we perceive and interpret the objective world in a subjective manner. In a way, our reality is somewhat of an illusion because our brain is constantly taking information, perceiving and coding it, and then producing a response that you can understand. When you “see” a tree, you aren’t actually seeing a tree, you’re seeing the perceived image generated by your brain from various stimuli. OK, that’s enough philosophic thinking for one day!

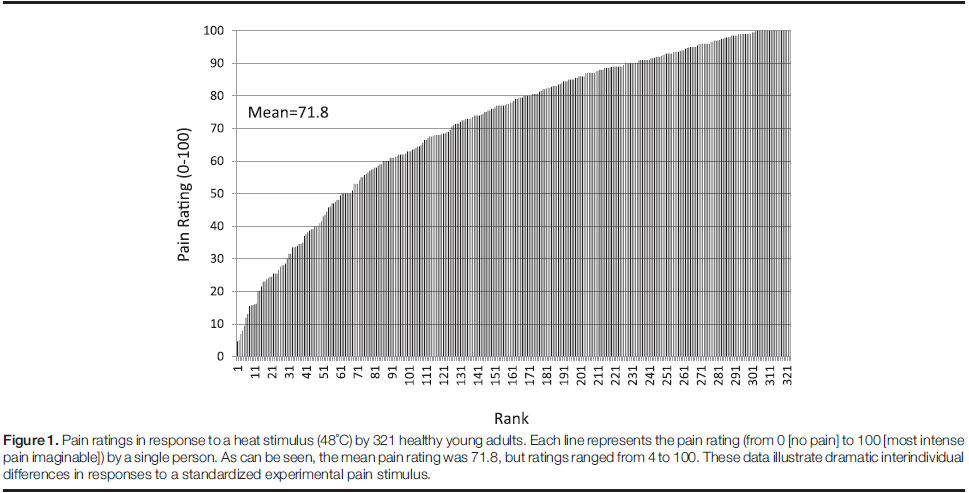

First, to further clarify how pain is an experience we can look to how people report varying levels of pain even when given an identical stimulus. One study demonstrated how 321 healthy adults were presented with a heat stimulus of 118 degrees Fahrenheit and asked to rank their pain on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst pain imaginable). Pain scores ranged from 4 - 100 even though the objective stimulus was identical for everyone (Fillingim 2017). This is but one example of how reported pain varies from person to person, making it a subjective experience.

Next, let’s investigate the notion that pain is caused by tissue damage. Injury in of itself is a whole separate topic for another blog, but let’s look at a couple examples of how “abnormal” and presumably pathological findings of various tissues don’t seem to correlate well with pain or function. A systematic review by Brinkinji and company wanted to see the prevalence of various spinal “pathologies” in asymptomatic adults across the lifespan. To do this, the researchers pooled 33 articles looking at 3,110 asymptomatic individuals. In order for a study to be eligible in this review, participants had to report no history of low back pain, and having no motor or sensory issues. All but 1 of the 33 studies used MRI to determine if a spinal pathology was present (1 used CT scan) and then stratified the prevalence of 8 pathologies across decades of life (20 -29 years old all the way to 80 - 89 years old). The study found supposed spine pathologies were quite common across age groups and increased with age despite being asymptomatic. If you’re 20 - 29 years of age, there’s a 37% chance you’ll have disk degeneration, and 30% chance you’ll have a disk bulge. On the other end, if you’re 80 - 89 years of age, there’s a 96% chance you’ll have disk degeneration, and 84% chance you’ll have a disk bulge, and remember, all these participants are asymptomatic! The authors concludes the study with a powerful quote “These findings should be considered as normal age-related changes rather than pathological processes” (Brinkinji et al. 2014). This paper calls into question if tissue abnormalities are really that out of the ordinary, and even if they are less common, when (if at all) do they become an issue?

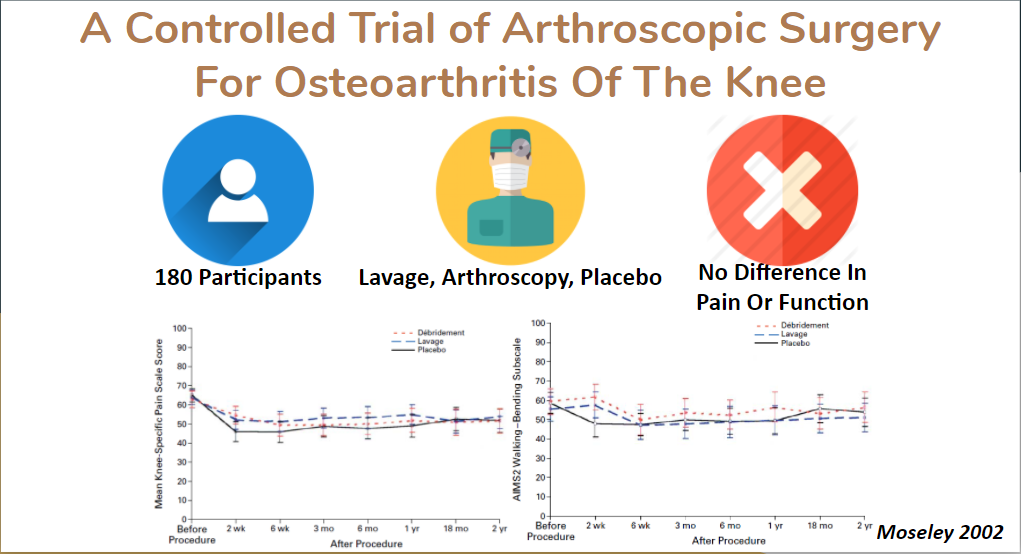

Another example that further complicates pain and tissue damage was a study conducted by Moseley and company. Moseley wanted compare pain and functional outcomes of various interventions for knee osteoarthritis. 180 participants were selected for this study and split into three treatment groups, arthroscopic debridement, lavage, and placebo surgery. If you’re scratching your head and wondering “what the heck is a placebo surgery” it’s exactly what is sounds like. 60 of the 180 participants went through a fake surgery, the ultimate placebo. The placebo group was given a short acting opioid and tranquilizer with oxygen enriched gas to simulate mild anesthesia, and rather than having medical instruments inserted into the knee joint (like lavage and arthroscopy), the surgeon simply made 1 cm long incisions as if they were going to carry out the surgery, sprayed water to simulate sounds and sensations, and then stitched the incision. Here’s the crazy part, the researchers found that there was no difference between these 3 groups in terms of pain and function outcomes anywhere from 2 weeks, to 2 years post study (Moseley et al. 2002). Similar examples of weak correlation between tissue abnormalities and quality of life are depicted in those with rotator cuff tears (Boorman et al. 2018). We also see the opposite can occur where people have no evidence of tissue damage or abnormalities and report pain and dysfunction (remember non-specific LBP?).

Why Pain Exists

In my opinion, the easiest way to conceptualize pain is as a threat perception system. It’s true, that pain is an evolutionary adaptation to protect you from suffering serious or even life threatening injuries. Imagine if when you put your hand on the hot stove (as most of us did as kids, even though our parents told us not to) that you didn’t feel anything. This is problematic because if you don’t have something to alert you and steer you away from this harmful stimulus then you can suffer serious consequences. This is especially true for our ancestors who didn’t have access to the wonders of modern medicine. A deep enough cut, a bite from a snake, or a muscle tweak could’ve been the end of you back in the day. So, pain evolved to alert us when something potentially bad is happening, and then influence future behavior in order to protect us from a future encounter with that stimuli (Broom 2001). This is an important feature of pain that should be acknowledged however, as discussed earlier, the pain you experience is dictated by biological, psychological, and social factors. This means that you can perceive pain without a biological stimulus that threatens you. This is troublesome because we’re generally taught that pain always means something is wrong, damaged, or broken, and that if you continue doing the thing you believed caused your pain you’re going to make things worse. If that’s true, what do we tell the 90% of people who have non-specific LBP? What do we tell people who (rare as this may be) have phantom limb syndrome, because there is no tissue to be damaged, the limb doesn’t exist anymore, which Dr. Foell brilliantly explains in this Tedx Talk. Another extreme example of how pain isn’t purely a biological phenomenon is people who experience trauma in high stress environments, like a soldier not noticing they were shot in a gun fight until they’re checked by a medic hours later. Pain without injury or tissue damage, and injury or tissue damage without pain, these two circumstances illustrate how pain isn’t purely a biological phenomenon. The question then becomes “when should we be concerned about pain”? First in foremost, you should never simply ignore what your body is telling you, it’s important to acknowledge what’s happening whether you’re a coach, physical therapist or even the person experiencing the sensation. What we want to avoid is making the situation worse while also being aware of any red flags such as loss of sensation or function, visible swelling or deformation, and constant sharp and debilitating pain.

Perception

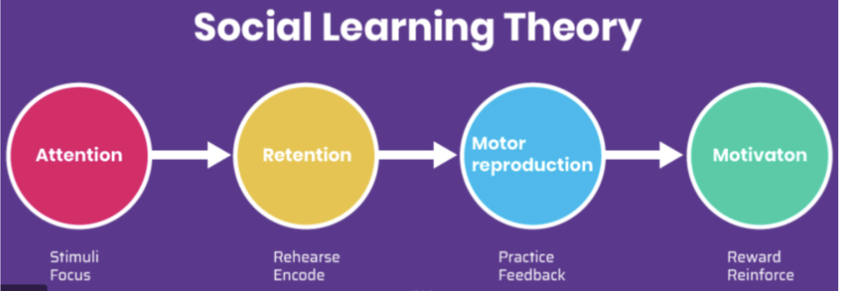

So we understand that pain is an evolutionary adaptation to protect us, but what happens when the psychological and social aspects of the BPS Model dominate the experience of pain? This can lead to several negative consequence such as avoidance or learned behavior that isn’t necessarily harmful. One of the risk factors for developing chronic pain is having a parent with chronic pain. This shared experience is demonstrated in great detail by Stone and colleagues. Stone wanted to see how children’s perception of parental pain impacted their pain levels. The researchers surveyed 138 children (mean age = 14) with functional abdominal pain and investigated how the children’s pain levels correlated to their perception of how much pain their parents were experiencing. The researchers had the children and parents report their pain using various surveys and the children were instructed to monitor their perception of their parents pain for 7 days while also reporting their daily abdominal pain levels. The study found that children who observed more pain related behavior from their parents had greater pain interference, meaning pain had a more debilitating impact in their day to day routine (Stone et al. 2016). This shared experience of pain makes sense if you consider Social Learning Theory, which states that new behaviors can be learned by watching or imitating others. Another example was a meta analysis by Higgins which looked at how the chronic pain in parents influenced the presence of chronic pain in their offspring. 59 studies were included in this analysis and analyzed over 4.5 million participants. The researchers concluded that “This comprehensive and rigorous mixed-methods systematic review and syntheses indicates that overall, offspring of parents with chronic pain have poorer outcomes in the areas of pain, health, psychological, and family functioning as compared with offspring of parents without pain” (Higgins et al. 2015).

Pain Catastrophizing

The path of pain and perceptions has the potential to lead a person to pain catastrophizing. This means that the person assumes the pain they are experiencing is the worst thing possible. Someone who catastrophizes pain might think they tore their meniscus of their knee if it’s a little sore, or believe they have a tumor in their back because they have some mild discomfort. Catastrophizing is caused by something known as fear avoidance, in which a person has the potential to code a certain stimulus or experience as dangerous. As we learned, your pain experience is influenced by several factors, such as learned behaviors from family members. This concept also applies to friends and professionals you trust (coaches, doctors, etc.). Knowing this, what do you think happens when someone goes to the doctor with a complaint of LBP? Perhaps they get a MRI and it’s confirmed they have a herniated disk (we mentioned the prevalence of such findings earlier, so it wouldn’t be surprising to find in the first place). The doctor might instruct the person to avoid certain types of activity or movement that is commonly perceived as having potential risk for damaging the structures of the spine. The individual then expresses their concern to their family, who further reinforces the idea that they should avoid certain movement since they too were taught similar behaviors. All these experiences, perceptions, learned behaviors, and biological phenomenon lead the individual to believe they should avoid anything that causes pain in that respective area because if they don’t, something bad will happen. So, to reinforce this, the brain modifies your response to certain stimuli and subsequent behavior, which further reinforces all of the person’s fears and assumptions. We call this series of events in which pain leads to extremely negative perception, catastrophizing, and subsequent avoidance The Fear Avoidance Model (Nelson et al. 2015).

Living in the Gray

So, the TLDR of this whole article in case you zoned out half way through!

Pain impacts several people across the globe and effects quality of life and physical activity.

Our understanding and definition of pain is ever changing.

Pain is a complex, multi-factorial, subjective experience, influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors.

Pain doesn’t necessarily equate to tissue damage or injury and vice versa.

Pain is an evolutionary adaptation for threat perception.

Pain can be created or exaggerated by perceptions of one’s environment and those around them.

Pain can be reinforced through various factors, causing avoidance behaviors, which may have negative consequences.

There’s a lot we still don’t know about pain, and even more so, there are things we don’t know that we don’t know (let that one cook your noodle for a minute). Like most things involving people, this subject isn’t clear cut. It’s messy, the lines are blurred, and there’s a lot of “maybes” and “it depends”. Becoming comfortable with this uncertainty, in my opinion, is the hallmark of a true professional! We’ll continue to do our best, update our knowledge, and continue striving towards a better understanding of how pain and perceptions work so we can help those in pain. In my next blog, I’ll be talking about pain as it pertains to exercise, and what you can do as someone experiencing it, or as a coach looking for program design guidance, so stay tuned!

References:

About IASP. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.iasp-pain.org/AboutIASP/

Boorman, R. S., More, K. D., Hollinshead, R. M., Wiley, J. P., Mohtadi, N. G., Lo, I. K., & Brett, K. R. (2018). What happens to patients when we do not repair their cuff tears? Five-year rotator cuff quality-of-life index outcomes following nonoperative treatment of patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 27(3), 444-448. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.10.009

Brinjikji, W., Luetmer, P., Comstock, B., Bresnahan, B., Chen, L., Deyo, R., . . . Jarvik, J. (2014). Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 36(4), 811-816. doi:10.3174/ajnr.a4173

Broom, D. (n.d.). Evolution of Pain. Royal Society of Medicine International Congress Symposium Series.

CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. (2019, August 28). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

Duffy, T. P. (2011). The Flexner Report ― 100 Years Later. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 269-277.

Engel, G. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129-136. doi:10.1126/science.847460

Fillingim, R. B. (2017). Individual differences in pain. Pain, 158. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000775

Foell, J. (Director). (2017, September 22). Phantom Limbs and Perceived Pain [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7-EpZcKgufM

Germ Theory. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://science.jrank.org/pages/3035/Germ-Theory.html

Higgins, K. S., Birnie, K. A., Chambers, C. T., Wilson, A. C., Caes, L., Clark, A. J., . . . Campbell-Yeo, M. (2015). Offspring of parents with chronic pain. Pain, 156(11), 2256-2266. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000293

A history of psychiatry : From the era of the asylum to the age of Prozac : Shorter, Edward : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming. (1997, January 01). Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/historyofpsychia0000shor/page/76/mode/2up

IASP Announces Revised Definition of Pain. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/NewsDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=10475

IASP Terminology. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698

Kendroud, S., Murray, I., Hanna, A., & Fitzgerald, L. (2020). Physiology, Nociceptive Pathways.

Koes, B. W., Tulder, M. W., & Thomas, S. (2006). Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Bmj, 332(7555), 1430-1434. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7555.1430

Moseley, J. B., O'malley, K., Petersen, N. J., Menke, T. J., Brody, B. A., Kuykendall, D. H., . . . Wray, N. P. (2002). A Controlled Trial of Arthroscopic Surgery for Osteoarthritis of the Knee. New England Journal of Medicine, 347(2), 81-88. doi:10.1056/nejmoa013259

Nelson, N., & Churilla, J. R. (2015). Physical activity, fear avoidance, and chronic non-specific pain: A narrative review. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 19(3), 494-499. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.02.001

Overcoming Barriers to Physical Activity. (2020, April 10). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/adding-pa/barriers.html

Pain: Definition of Pain by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also meaning of Pain. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/pain

Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults - United States, 2016. (2019, September 16). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6736a2.htm

Stone, A. L., & Walker, L. S. (2016). Adolescents’ Observations of Parent Pain Behaviors: Preliminary Measure Validation and Test of Social Learning Theory in Pediatric Chronic Pain. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsw038

Strickland, C. M., & Patrick, C. J. (2015). Biomedical Model. The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology, 1-3. doi:10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp476

Also, a special thank you to the Barbell Medicine Crew for introducing me to this field and content!