The Complexities of Obesity, A Modern Perspective Pt. 2 Accurately Assessing Obesity

Reading Time: 15 Minutes

In part 1 of this 3 part blog series, we discussed exactly what obesity is, its prevalence in the American and global population, its causes, and how it impacts health. The goal of this blog is to outline assessment criteria for determining obesity. Note that while these tests / protocols can help determine obesity, no test is perfect, and each client / patient should be evaluated on an individual. Additionally, this is not a medical diagnosis, nor medical advice. If you have any medical concerns regarding obesity please contact your primary health care provider.

A Quick Stats Lesson.

I’ll be the first to admit, I’m no expert when it comes to statistics. However, I’m fortunate enough to have some exposure to stats due to my education, exercise science research, and general curiosity. It’s important to talk about some key terms regarding statistics before we dive too deep into some of the inclusion criteria for obesity. There are a few things to consider when looking for a good test or assessment whether its in medicine or personal training.

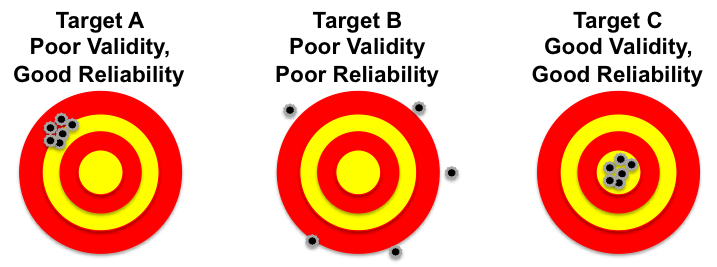

Validity: Does your assessment actually measure what it’s intended to measure? For example, we know that X-Rays are extremely valid when it comes to determining broken bones, however, you wouldn’t use an X-Ray to determine if you had a fever because X-Rays don’t measure temperature. The tool (X-Ray) works, but in the context of temperature it would not be a valid tool, because it isn’t measuring what it’s proposed to measure.

Reliability: Are the results of your assessment repeatable over time? If your measurements have fluctuations with large margins of error it can skew your results. Generally when discussing reliability, we talk about 2 different types.

Inter-Rater Reliability - Can two people perform the same test on a given person and get the same or similar results? For example, If there is 1 client and you want to measure their blood pressure, can Trainer A & Trainer B get the same or similar results.

Test-retest Reliability - Can a single rater produce the same or similar results on the same person? For example, say you’re a coach and you’re measuring someone’s heart rate. You conduct the test, wait a minute, and see if you can repeat the results under the same conditions.

Practicality: Can your test be done in a realistic manner? While this isn’t a requirement, it does make testing more practical depending on your setting. For example, a DEXA scan is currently the gold standard for assessing body composition, however if you’re a coach at a local gym chances are you don’t have access to one, and even if your client could get one, they are quite expensive.

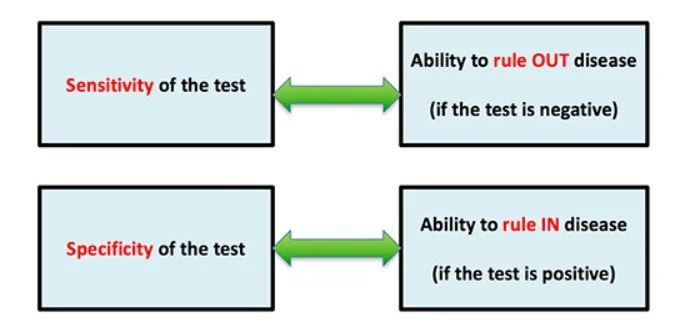

Specificity: A highly specific test would limit the amount of false positives, meaning fewer people being marked as having a disease when they are otherwise healthy. Imagine a faulty MRI machine that worked sometimes, but also highlighted ACL tears on healthy individuals. It’s true that sometimes the machine is accurate, but often times it flags people that are otherwise healthy.

Sensitivity: A highly sensitive test would limit the amount of false negatives, meaning fewer cases of disease are missed. So say you did a blood test for diabetes and the test was extremely sensitive. If you got a negative test result the likelihood that you have the disease is very unlikely.

The example I like to use when comparing these 2 is that of a fishing net. Image you want to catch a certain fish in a lake near your home, all of which are identical in size. Think of specificity as the holes of the fishing net, and sensitivity as the entire size of the net. If I have a test that is highly specific, but has low sensitivity (perfect size holes in the net, but a small net overall) this means when you catch a fish in this net, you can almost guarentee it’s the fish you’re looking for, but since the net isn’t very big, you’re missing a big portion of the fish inside the rest of lake. On the flip side imagine a test that is highly sensitive but not very specific (large net, but the holes are bigger than size for the fish you want). In this example, since the net is so big chances are the fish you want is inside the net! However, since the holes for the fish you want are a bit larger, some fish are going to slip past the net and not get caught when they should’ve.

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Now that we have some general understanding of statistics, let’s dive into a few tests and assessments we can use or look at to help determine if a client is a healthy candidate for weight loss. The first item we have to talk about of course is Body Mass Index, or BMI.

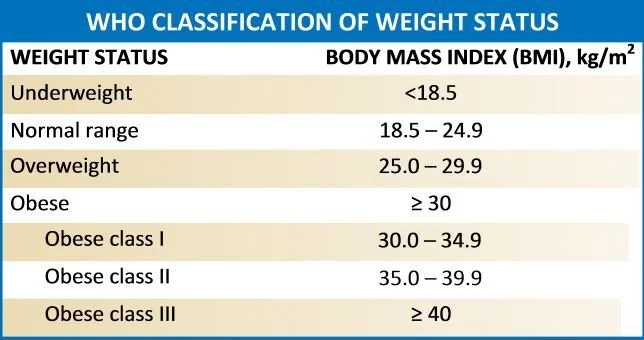

BMI was first created by a Belgian mathematician named Adolphe Quetelet in 1832. Quetelet was trying to figure out the general size and proportions of the average man. To do so, he created what was known as the Quetelet Index as a way to correlate a person’s height to their weight. This didn’t really pick up in popularity again until the 1970’s when Ancel keys was trying to determine ways to quantify health. In 1972, Keys started using a measurement known as Ideal Weight for medical evaluations, which was a simple height to weight ratio in the hopes of gathering data to determine if patients were at higher risk for certain diseases and a potential shorter life span. Unfortunately, a general height to weight ratio didn’t correlate well with disease processes, so Ancel tried adding another measuring point to this correlation to help stratify his measurements in the hopes of making predictive values more accurate. Keys tried to correlate a measurement of the elbow to determine body frame size, and then determine if this could better predict health in combination with a person’s height and weight. This too had several issues and didn’t correlate well. Keys then decided to bring back Quetelet Index and named it BMI. This formula was ultimately adopted by the WHO 1990’s. From there, BMI was separated into various categories to classify people’s health. In general, a BMI under 18.5 is considered having underweight, a Normal range for BMI is 18.5 - 24.9, having overweight is 25 - 29.9, and having obesity and its various classifications is having a BMI of 30+.

Proposed Issues with BMI

Let me be abundantly clear, BMI is by no means a perfect exam, nor should it be used in isolation for determining if someone is a good candidate for lowering their body fat. However, I do believe BMI can be a valuable, user friendly screening tool to prompt further investigation. Let’s break down some of the common criticisms concerning BMI and why they may not be true.

BMI and proposed racism: It is true that Pre 1990’s, the majority of BMI data was conducted on Caucasian men. So there are concerns that this measurement doesn’t account for women or people of different ethnic groups. This is a fair criticism considering that different disease processes impact different sexes and ethnic groups in different ways. Take sickle cell anemia or breast cancer as two simple examples. However, when look at more recent BMI data including men and women and people of various ethnic backgrounds we get a test that is highly specific but low in sensitivity.

Specificity true negative test: This means if you have a BMI of 30 or greater, chances are it’s not a false positive and that further evaluation would be warranted to determine if someone is a healthy candidate for weight loss. in fact when testing BMI across ethnic groups 99% of Men and 95% of women who had a BMI of 30 or greater were considered having excess adiposity and would benefit from losing body fat. This data again is from men and women across various ethnic groups and ages.

Sensitivity True positive test: The issue with BMI is by using 30 as a cut off point for having obesity, we actually miss several people that have excess adiposity. Using BMI alone only caught 36% men, 49% women who were classified as having excess levels of adiposity. This means that BMI in isolation actually misses, or underpredicts 2/3 of men and 1/2 of all women who are carrying to much body fat despite having a BMI under 30. Contrary to popular belief, this means that BMI isn’t over estimating people who potentially have obesity, in fact it’s severely underestimating it.

The key TLDR here. If someone has a BMI of 30 or more and you had to bet, there’s a high likelihood that they have obesity. However, if they’re BMI is under 30, there’s a high chance that you’re missing people who can still have obesity.

Coach’s Bias: As health and fitness professionals, we may do BMI on ourselves and have a BMI of 30 or more despite being healthy and having low levels of body fat and a high amount muscle mass. The example I give here is Running back for the NY Giants, Saquon Barkley (AKA Saquads Barkley). If you know him, this man has tremendous amounts of muscle mass. However, at 6 ft. tall and weighing 235 lbs. he has a BMI of 32, which technically means he has obesity. This one of those examples where you will have outliers that certainly aren’t obese. The thing I remind coaches is that most people aren’t Saquon Barkley, in fact most people aren’t like coaches. Remember, only 24.2% of Americans report meeting the minimum ACSM guidelines for physical activity, so most people aren’t active or living a healthy lifestyle.

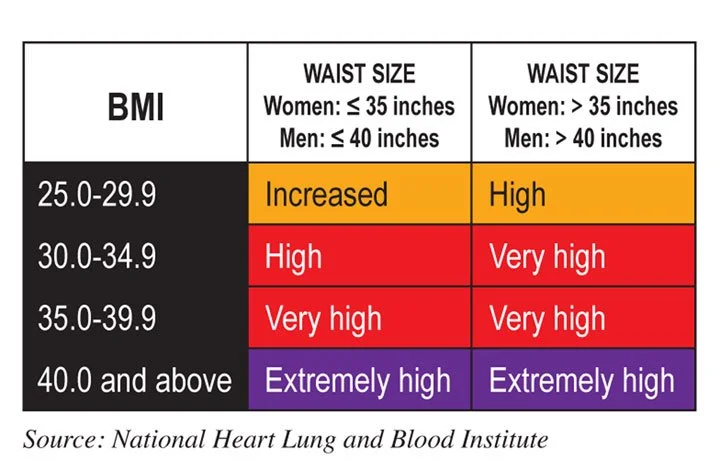

The important thing to remember is that BMI is just a screening tool and shouldn’t be used in isolation. If you have a client who has a BMI of 30 or more it should prompt you to investigate further. As mentioned above, BMI unfortunately has poor sensitivity, so another test is needed to help increase it. Luckily we have some great research about waist circumference!

Waist Circumference

Make it stand out

Waist circumference is an anthropometric measurement that identifies general abdominal adiposity (Klein et al. 2007) We have good evidence from over 600,000 subjects demonstrating that one’s waist circumference has great predictive power for all cause mortality (Cerhan et al 2015). As discussed in pt.1 of this blog series, abdominal based adiposity appears to have a strong correlation with obesity and overall poor metabolic health. This is due to the fact that excess, chronically held adiposity acts like a pro-thrombotic secreting gland, which promotes various forms of cardiovascular disease among other issues. A study from Janssen et al demonstrated that a waist circumference greater than 40 inches for men and 35 inches for women (especially combined with a BMI of 30 or more) led to higher risk of disease (Janssen et al. 2002).

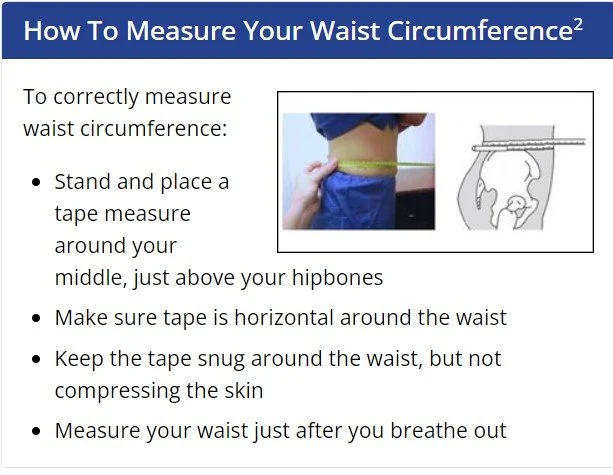

Depending on where you read, there are various anatomical locations for where to take the waist circumference measurement. Because of the large body of research and number of participants across various studies, I like to use the CDC’s version of waist circumference which uses the apex of the illiac crest as the starting landmark (CDC).

Body Fat Percentage

Another useful measurement to help assess excess adiposity is to simply measure people’s body fat percentage. Due to practicality sakes, I’m only going to discuss Skinfold tests and Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) since DEXA scans and underwater weighing are not practical for most coaches and general health practitioners. For skin folds I recommend the Jackson Pollock 3-site method as it has credible validity and reliability. Accuracy of BIA will fluctuate based on the device used among other factors.

When assessing body fat, the cut off points of 25% and 32% for men and women respectfully are used to denote an excess amount of adiposity and potentially having obesity.

Jackson Pollock 3-site method.

Skin folds are designed to measure sub-cutaneous fat and then extrapolate estimates of body fat based on the size of the folds and the subject’s age. The Jackson Pollock method takes 3 measurements per person. For men the chest, abdomen, and thigh are utilized. For women the triceps, suprailliac, and thigh are used. Each site is done twice with an acceptable margin of error between measurement of +-2 mm. This test does have limitations such as user error, skin elasticity, age, hydration, among other factors. However, if done in by a skilled individual under proper settings it can be have great test-retest reliability and solid validity compared to DEXA scans (Aandstad 2014).

Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis, or BIA, is another popular tool for measuring body fat that can be somewhat accurate if done in proper settings. BIA works by sending a low voltage current through your body at various points of contact. The rationale is that different types of tissues, structures, and materials of the body (water, fat, muscle, and bone) all have a different resistance to flow, thus are able to be measured in proportions. It’s important to note that not all machines for BIA are created equal. For example the handheld BIA here only produces a current to measure the upper body and makes estimates for the lower body. Versus an InBody machine which is much more sophisticated and can analyze your body by segments. Since this technology works on Impedance, several factors can influence one’s reading such as skin temperature, hydration, menstrual cycle, being pregnant, metal on or inside of your body, among other factors. Similar to skin fold calipers however, if done in appropriate settings, you can produce a somewhat accurate measure compared to the gold standard DEXA with a margin of error of approximately +-3.5% body fat

Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic Syndrome is a collection of conditions that negatively impact your health (Huang 2009). An individual is said to have metabolic syndrome if 3 or more of the inclusion criteria below are present.

Waist Circumference: Men > 40 inches, Women > 35 inches.

Blood pressure: Greater than 130 / 85 mmHg

Fasting Triglyceride: Level over 150 mg/dl

Fasting High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL): Level less than 40 mg /dl for men, and 50 mg/dl for women

Fasting Blood sugar: Greater than 100 mg / dl

Knowing this collection of information is helpful because metabolic syndrome has a a high correlation with rates of obesity.

We Can Assess, Now What?

As a reminder, the tools outlined above are simply that, tools. They are not official diagnostic criteria and clients should consult with their physician. However, by utilizing these tests, we can get a good understanding of if someone may be a good candidate for weight loss to improve their health and quality of life. Remember these tests are not perfect, and sometimes people may test positive and will have no health issues and vice versa. In the 3rd and final part of this blog series we will go over ways to improve people’s health who are dealing with obesity.

References

Aandstad, A., Holtberget, K., Hageberg, R., Holme, I., & Anderssen, S. A. (2014). Validity and reliability of bioelectrical impedance analysis and skinfold thickness in predicting body fat in military personnel. Military Medicine, 179(2), 208–217. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed-d-12-00545

Blackburn, H., & Jacobs, D. (2014). Commentary: Origins and evolution of body mass index (BMI): Continuing saga. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(3), 665–669. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu061

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, June 3). Assessing your weight. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/index.html

Cerhan, J. R., Moore, S. C., Jacobs, E. J., Kitahara, C. M., Rosenberg, P. S., Adami, H.-O., Ebbert, J. O., English, D. R., Gapstur, S. M., Giles, G. G., Horn-Ross, P. L., Park, Y., Patel, A. V., Robien, K., Weiderpass, E., Willett, W. C., Wolk, A., Zeleniuch-Jacquotte, A., Hartge, P., … Berrington de Gonzalez, A. (2014). A pooled analysis of waist circumference and mortality in 650,000 adults. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 89(3), 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.11.011

Chiang, I.-C. A., Jhangiani, R. S., & Price, P. C. (2015, October 13). Reliability and validity of measurement. Research Methods in Psychology 2nd Canadian Edition. https://opentextbc.ca/researchmethods/chapter/reliability-and-validity-of-measurement/#:~:text=Reliability%20is%20consistency%20across%20time,on%20various%20types%20of%20evidence.

Department of Health. Disease Screening - Statistics Teaching Tools - New York State Department of Health. (n.d.). https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/chronic/discreen.htm#:~:text=Sensitivity%20refers%20to%20a%20test’s,have%20a%20disease%20as%20negative.

Huang, P. L. (2009). A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome. Disease Models & Mechanisms, 2(5–6), 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.001180

Janssen, I., Katzmarzyk, P. T., & Ross, R. (2002). Body mass index, waist circumference, and health risk. Archives of Internal Medicine, 162(18), 2074. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.162.18.2074

Klein, S., Allison, D. B., Heymsfield, S. B., Kelley, D. E., Leibel, R. L., Nonas, C., & Kahn, R. (2007). Waist circumference and cardiometabolic risk: A consensus statement from Shaping America’s Health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, the Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Association*. Obesity, 15(5), 1061–1067. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.632

Romero-Corral, A., Somers, V. K., Sierra-Johnson, J., Thomas, R. J., Collazo-Clavell, M. L., Korinek, J., Allison, T. G., Batsis, J. A., Sert-Kuniyoshi, F. H., & Lopez-Jimenez, F. (2008). Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. International Journal of Obesity, 32(6), 959–966. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.11

What is the quetelet index. (BMI). Duquesne University School of Nursing. (2019, March 1). https://onlinenursing.duq.edu/doctor-nursing-practice/quetelet-index-bmi/#:~:text=Quetelet’s%20premise%20was%20based%20on,body%20mass%20by%20height%20squared.